Hello Fireshed community,

Today marks exactly two years since firefighters at last contained the historic Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon Fire on August 21, 2022.

Families, communities, forests and watersheds in Northern New Mexico are still recovering from the destructive wildfire. In fact, the Santa Fe National Forest is hosting two public meetings next week to present and gather public input on recovery efforts and long-term recovery planning.

Meanwhile, forest, water, and fire managers are rebuilding support for prescribed fire as an essential land management tool – one not without risk, but key to reducing future risk of catastrophic wildfires.

This Wildfire Wednesday features a review of the Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon Fire, including:

Best, Maya

How the Fire Began

Hermit’s Peak, April 10, 2022. Source: U.S. Forest Service

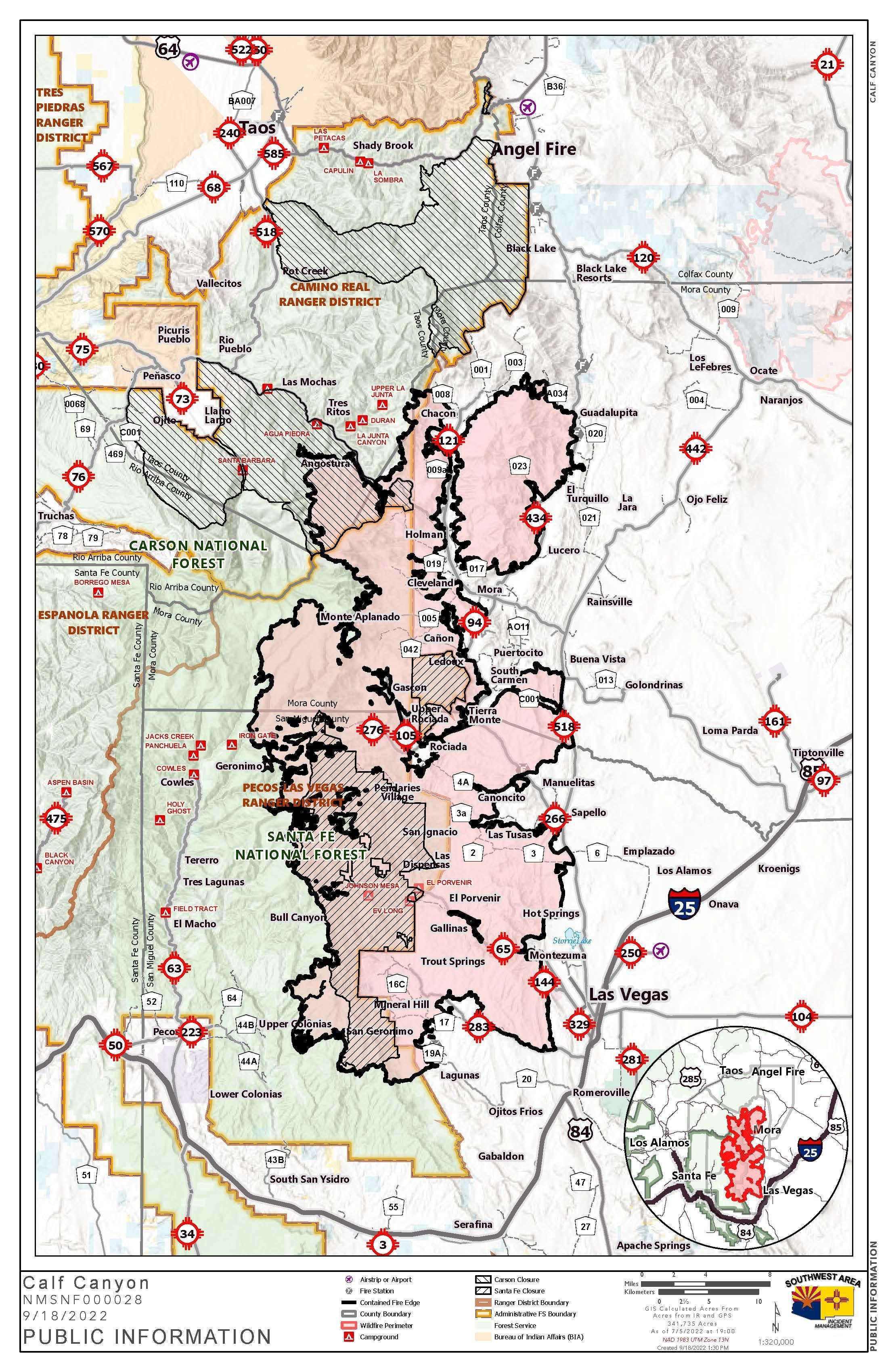

HPCC Wildfire Boundary. Source: Inciweb

In April 2022, a Forest Service prescribed fire just outside of the Pecos Wilderness area of the Santa Fe National Forest became the Hermit’s Peak wildfire when erratic winds carried embers outside the boundary of the planned burn area and ignited multiple fires in surrounding forests dried out from severe drought.

About two weeks later, the Calf Canyon Fire began spreading on National Forest land nearby when a pile burn ignited by the Forest Service in January resurfaced. The pile had smoldered underground for months through several snowstorms, an event “nearly unheard of until recently in the century-plus of experience the Forest Service has in working on these landscapes,” Forest Service leaders wrote in a review of the escaped prescribed fires.

The two wildfires merged due to unprecedented wind events and historically dry fuels and soils and burned more than 530 square miles over four and half months, until firefighters contained the blaze in late August.

The Costly Road to Recovery

Mora Valley, June 28, 2022. Source: Inciweb

The Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon Fire, the largest wildfire in New Mexico history, triggered evacuation orders for more than 27,000 people and destroyed over 900 structures, including 433 homes. Most of the land burned – 58% – was privately owned.

Because the Forest Service was responsible for igniting the fire, Congress and President Joe Biden allocated almost $4 billion to compensate victims of the fire and subsequent floods. As of July 2024, while still processing and receiving additional claims, the federal government had paid out 5,633 claims totaling $926.7 million.

Payments covered economic damages, up to five years of flood insurance coverage, and natural resource restoration projects for landowners. Additional recovery efforts in years following the burn have included aerial seeding of the burn scar and flooding prevention work by federal agencies and local organizations.

Post-fire Flooding: A Prolonged Disaster

High-severity wildfires burn not only vegetation but also soils, changing the chemical and physical properties of soil such that it becomes hydrophobic, or water-repelling. This reverses forests’ sponge-like ability to soak up rainfall and instead makes burn scars susceptible to debris flows and flash floods.

The Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon Fire damaged soil in over half the burn scar, causing floods that killed at least three people, washed out buildings and infrastructure, and contaminated the city of Las Vegas’s water supply with ash and debris in 2022. The National Weather Service received over 75 preliminary reports of flash floods and debris flows in the burn scar from June 2022 to June 2024. For multiple years following the fire, surrounding communities expect to be at elevated risk for flooding.

Prescribed Fires Remain a Crucial Tool for Reducing Wildfire Risk

The Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon Fire spurred the Forest Service to pause all prescribed burns pending a 90-day review of its national prescribed burn program. Forest Service Chief Randy Moore said the decision “reflected the growing recognition that extreme conditions resulting from drought, weather, dry fuels, and other climate change effects were influencing fire behavior in ways we had never seen before." The prescribed burn that became the Hermit’s Peak Fire had been ignited in “much drier conditions than were recognized,” the review found.

“We cannot guarantee that prescribed fires will never escape, but the alternative to using this proven tool is larger, more destructive wildfires.”

The review underscored the necessity of prescribed burns as one of the most effective tools for forest, fire and water managers to reduce the risk of catastrophic wildfires, protect watersheds, and increase the resilience of forests. Over a century of fire suppression in fire-adapted forests of the Southwest has, in combination with climate change, created conditions for high-severity wildfires that threaten people, property and drinking water sources and threaten forests’ ability to regenerate. Prescribed burns, on the other hand, facilitate a return to low-severity fires that promote forest health and increase firefighters’ success in safely managing fires. Of the about 4,500 prescribed burns conducted by the Forest Service annually, 99.84% have gone according to plan, the review noted.

The Forest Service resumed prescribed burning with updated guidelines aimed at further reducing the risk of escaped prescribed fires. New requirements include daily, higher-level review of prescribed burn plans; more localized weather data; heightened consideration of drought conditions in burn plans; long-term monitoring of burns; and more extensive public outreach about prescribed fires, among other changes.

Additional Resources

Visit the New Mexico Forest and Watershed Restoration Institute’s Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon Story Map for numerous maps, photographs, and graphics illustrating the spread and aftermath of the wildfire.

View this blog post in an easy-to-read PDF format on the Greater Santa Fe Fireshed Coalition’s Briefing Papers webpage. Other briefing papers on the webpage cover topics including:

Stewarding the Greater Santa Fe Fireshed

Source Water: Fire and the Santa Fe Municipal Watershed

Containing Wildfire: The Medio Fire Success Story

Pollinators and Wildfire

Post-fire Impacts

Forest Type Conversion

Fire History in the Greater Santa Fe Fireshed

NEPA

Insect Defoliation in the Greater Santa Fe Fireshed

The Intersection of Bird Habitat and Forest Restoration in the Southwest