Before we dive into today’s topic, we want to address something which is currently in the news:

As you may know, a shutdown of nonessential components of the federal government started today due to a lapse in congressionally approved funding. While it is unclear at this time how this will impact federal colleagues and partners, we hope to quickly return to being able to work with them because we know that New Mexico's wildfire crisis doesn't stop at fence lines - many of our communities and water sources are adjacent to or on federally-managed lands, and we need all hands on deck to meet the moment and continue moving toward being a fire adapted state.

Happy Wednesday, FAC community!

For today’s newsletter topic, we wanted to share an update to some information we provided back in 2021 related to cultural forest practices and the complex relationship humans have had with forest management for millennia. It is a common misconception that that the American West was “shaped entirely by natural forces” prior to arrival of Europeans; however, burning and logging have played a significant role across our landscape for nearly 15,000 years. Read on to learn more about these forest management techniques and the indigenous peoples who practice them today.

This Wildfire Wednesday features:

Cultural burning

Webinars

Toolkits

Recent publications

Have a great start to autumn,

Rachel

Cultural Burning

What is cultural burning?

““Cultural burning by Native Americans interconnected them not only to the land but to their animal, reptile, bird and plant spiritual relatives. Therefore, conducting a cultural burn relates to what they burned, how they burned it, and why they burned it”

Cultural burning falls within the broader category of intentional fire for community and resource resilience, a designation which also contains prescribed or controlled burns. “Cultural burning is separate and distinct from prescribed fire. While both forms of beneficial fire are essential to restoring good fire to the landscape, cultural fire has history, motivation, and meaning beyond the benefits it can reap for the environment” (Good Fire II, 2024).

Cultural burning is also a key component of traditional knowledge. “Reciprocity is a critical component of most Indigenous knowledge systems across the Tribes in the Columbia River Plateau, Intermountain West, and Great Basin and is one of the tenets of process-based restoration. Traditional knowledge systems convey principles of conduct for community members, pass down observations recorded through stories and songs, and describe the obligation to care for ecological systems as perpetual stewards” (An Indigenous Perspective of Fire, 2025). Within indigenous communities, cultural burning is “pertinent and substantial to the cultural livelihood”. Anthropologists have identified more than 70 different purposes for the intentional use of fire within ancestral indigenous and aboriginal cultures. There is also evidence that land areas used by Native Americans and subject to Indigenous fire management practices were more fire-resilient, even during climate periods that favored longer fire-free periods (NOAA, 2023).

History of cultural burning

State and federal government policies over the last 150+ years have targeted, banned, and put substantial logistical and legal strain on the use of cultural burning. “Sovereignty over lands, waters, and natural resources within their unique ancestral territories is one of the most critical retained powers for Tribes… Nevertheless, both federal and state governments can and do interfere with the exercise of such sovereignty” (Good Fire, 2021). Some barriers to cultural burning include:

Entities mistakenly treating cultural burning as prescribed fire (and therefore restricting it according to prescribed fire standards)

State and federal agencies asserting that they must “Permit” or “Allow” cultural burning on Lands of Territorial Affiliation.

The expertise of cultural fire practitioners in not formally recognized.

The enabling conditions necessary for landscape-scale, multi-jurisdictional stewardship are not yet in place (visit Good Fire II, page 13 for more detail).

In 2024, the Karuk Tribe championed, and the California Legislature passed, first-of-its-kind legislation that allows federally recognized tribes to practice cultural burning freely once they reach an agreement with the California Natural Resources Agency and local air quality officials. In February of this year, the Karuk Tribe became the first to enter into such an agreement. In this instance, that means that Cal Fire will no longer hold regulatory or oversight authority over the burns and will instead act as a partner and consultant, restoring the proper government-to-government relationship. There are still many barriers to indigenous communities exercising their sovereignty related to cultural burning, including some which are unique to the Southwest or have their roots in the complicated ‘trust responsibility’ of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. However, the successes by and lessons learned from our neighbors to the West can help us pave the way to wider use of this practice in New Mexico.

To learn more about cultural burning, visit the Indigenous Peoples Burning Network for more resources or watch this video by The Nature Conservancy “Revitalizing Cultural Burning practices, New Mexico and Beyond”.

Deep dive on cultural burning

Click on the buttons below to view academic papers and other articles detailing the history of cultural burning practices in the American West and current revitalization efforts. You can also register to attend an upcoming webinar from the Southwest Fire Science Consortium on the legacy of Indigenous cultural burning, showing that tree-ring fire history records from pine forests in Arizona and New Mexico demonstrate that Indigenous foragers, pastoralists, and farmers influenced Southwestern fire regimes.

Articles

Publications

Events

Cultural burning success stories

Indigenous Knowledges and Sciences as Best Available Scientific Information

Best Available Scientific Information (BASI) is defined as science that is accurate, reliable, and relevant. Indigenous Knowledges and Sciences (IKS) are place-based, culturally relevant knowledge that has been collected and carried down by Tribes and Indigenous Peoples from generation to generation. The wisdom contained within the broad scope of IKS is accurate, reliable, and relevant and is therefore qualified as BASI that can be used by land managers and researchers. Researchers and professionals need to recognize that the dimensions of specialization, personal experience, and transmission of IKS are diverse and complex, and understand that the information gathered by Indigenous Peoples is collected and communicated in different ways. Immense variation is present among Indigenous cultural roles, languages, and oral histories, as well as in methods of obtaining information. Ultimately, the findings obtained and documented through IKS belong to the people of that Indigenous Nation. These truths all need to be considered and respected when engaging with IKS as BASI.

The following story comes from an April 2025 article, Bringing ‘Good Fire’ Back to the Land

The Yocha Dehe Wintun Nation has recently revived its tradition of cultural burns. Every fall, the tribe holds Leok Po days, which means “good fire,” on Yocha Dehetribal lands in the Cache Creek Nature Preserve in Northern California. Melinda Adams, San Carlos Apache Tribe member and geography and atmospheric science professor at the University of Kansas, has come to help. She ties tule stalks into forearm-length bundles, preparing them as fire-carrying torches: “It’s significant,” she says, “because it’s one of the plants tribes use historically.” She calls these practices “indigenuity — Indigenous genius.”

Adams experiences the ceremony as deeply restorative — not just for the land but for herself, her community and her connection with her ancestors. “We’re not just healing the land ecologically and doing good stewardship work that’s eventually going to regenerate the plant communities,” she says. “We’re also healing ourselves as people, relearning our ways.”

For her, reviving cultural burns is also a reclamation and cultural revitalization. Every cultural fire practitioner she knows works with Native youth. “Whether we document it or not, we all make sure these cultural lessons are passed on to the next generation,” she says. “For a long time, it wasn’t safe to be Native. But cultural fire is a way of returning to the landscapes we were once punished for stewarding. When we gather for a burn, we reclaim our place.”

………………………….

In 2021, we published a story from the Mono Tribe on how cultural burning is being practiced and what lessons it holds for the future of the forest (see video). California banned cultural burning back in 1850 as part of legislation designed to forcibly remove Indigenous people from their ancestral lands. In an update to that story, this article explores how, since the California ban was lifted in 2022, the Tule River Indian, North Fork Mono, and Tübatulabal Tribes are working to return fire to Giant Sequoia groves. While only two off-reservation cultural burns have taken place in the giant sequoia range, the tribes and their partners are hopeful that these first steps will build widespread support for cultural burning. Click here to read the article “Banned for 100 years, cultural burns could save sequoias”.

………………………….

In the Western U.S., extreme wildfires are damaging tribal lands. Changing climatic conditions have only made the situation more dire. “That’s why the Washoe Tribe of Nevada and California is working to reintroduce intentional, cultural fire. These are once-banned burning practices they use to restore the health of their forests and plants… Cultural fires are restorative, not destructive. They’re typically done on a smaller scale to take care of traditional medicine plants or other cultural resources that rely on fire… ‘For example, the Washoe Tribe, our first two burns were burning a willow patch,’ said Rhiana Jones, director of the Washoe Tribe’s environmental protection department. ‘Washoes are famous for their baskets, making beautiful baskets. So when you burn the willows, they grow back better, straighter, with less secondary nodes’... ‘A lot of what we're doing here is trying to return to that different style of fire that allows us to actually promote our ecosystems, promote our cultures’ said Brandon Cobb, who’s Cherokee and a program manager with The Nature Conservancy.” Read more about the Washoe Tribe’s use of cultural burning in “The Washoe Tribe brings back cultural fire to restore forests, plants amid climate change”

Ancestral Logging Practices

The original wildland-urban interface in New Mexico was on the Jemez Plateau nearly 12,000 years ago where inhabitants practiced a form of selective logging. “Life on the Jemez Plateau required all the fine fuels that villagers could get their hands on. In roof construction alone, villagers cut hundreds of thousands of small-diameter timbers for supportive vigas, while understory growth went for fuelwood. Outside of villages, trails and agricultural fields acted as firebreaks.” There were actually more fires burning on the Jemez Plateau during this time compared to today, however, in part due to these forestry practices the fires were small and low in severity. Visit this 2017 High Country News article or read the paper below to learn more!

Elsewhere in the Southwest, Indigenous communities have historically harvested timber for fire fuel and construction materials. From the wooden support beams used in the Ancestral Puebloan sites of Wupatki, the cliff dwellings of Walnut Canyon, and Elden Pueblo, to contemporary maintenance and care of home and communal structures in Hopi villages, lumber has sustained northern Arizona’s Indigenous communities. View this archived article from Northern Arizona University to read more.

Additional Resources

Cultural Burn Pathway Workbook

The First Nations Emergency Services Society (FNESS) and the Indigenous Leadership Initiative (ILI) released the Create a Cultural Burn Pathway workbook, which contains seven worksheets that walk communities through the development of a strong cultural fire program—no matter what stage they are in. The workbook aims to help Indigenous Nations create cultural burn programs that reduce wildfire risk and revitalize a core part of our relationship with the land.

Cultural fire is culture and location specific. So instead of a prescriptive approach, each worksheet poses a set of questions and prompts that can be answered collectively. Worksheets 1,2, and 7 are for a broad cultural burn pathway whereas worksheets 3,4,5, and 6 are for specific burns.

Webinars

A Science-Management Partnership to Reduce Human-Caused Large Wildfires in the Southwest: Lessons Learned and Pathways Forward

Wednesday, Oct. 15, 12:00 PM

This webinar from the Southwest Fire Science Consortium will offer lessons learned from an assortment of Southwest-based studies on the social and ecological factors that drive human-caused wildfires and offer pathways forward for research findings to be implemented to reduce human ignitions in the future.

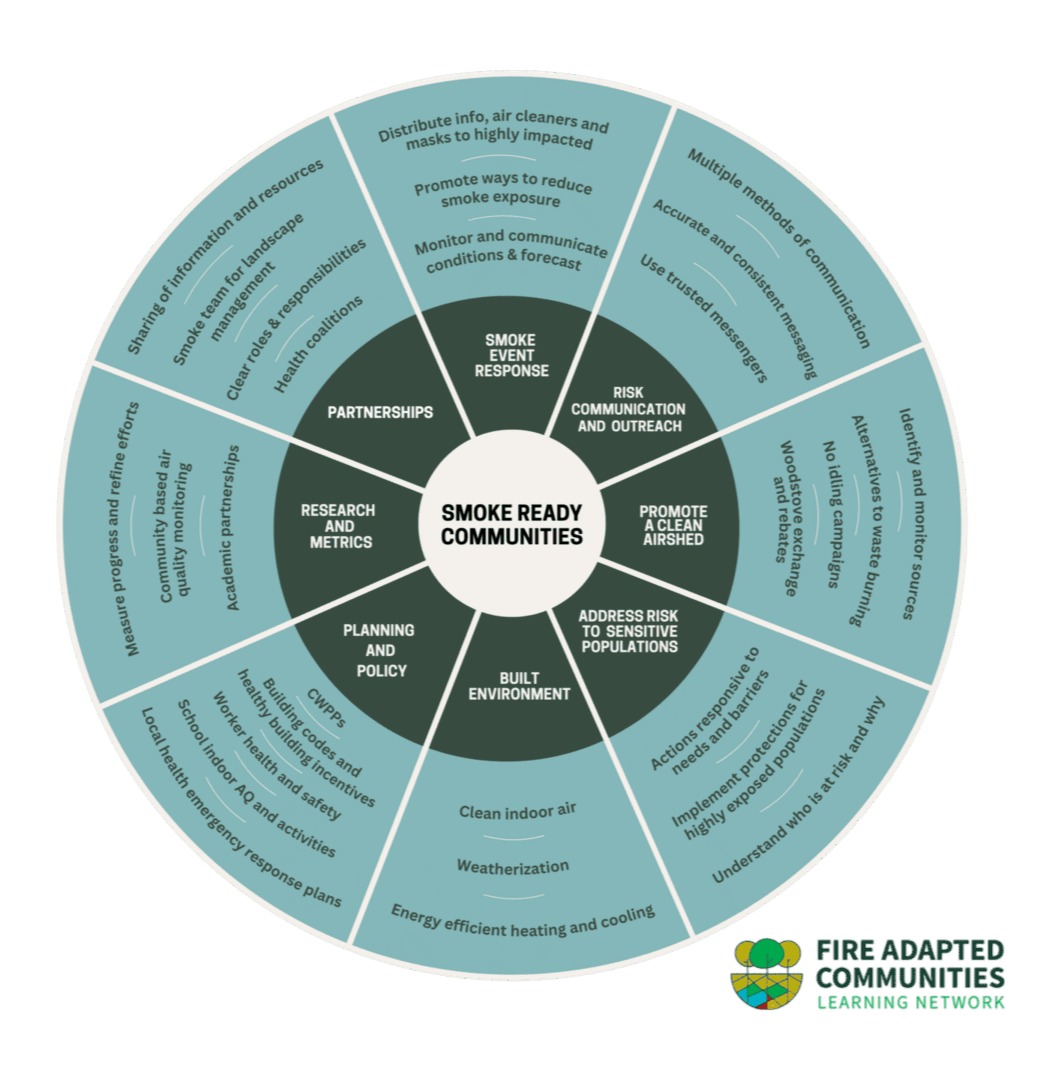

Reminder: Smoke Ready Communities Materials Release

Thursday, Oct. 9, 12:00 PM

Join the Fire Adapted Communities Learning Network and Liz Walker, PhD, for an informational webinar all around smoke ready communities! During this hour-long webinar we will discuss the "why" of including wildfire smoke in your FAC efforts and conduct an overview of the new smoke ready graphics & accompanying materials.

View the materials here: https://fireadaptednetwork.org/new-resources for-smoke-ready-communities/

CWPP Toolkit

In early 2024, FACNM released a short-form guide to help communities get started with writing or updating Community Wildfire Protection Plans (CWPPs). Now, CalFire with funding from California Climate Investments has produced a comprehensive CWPP toolkit with a video guide, a downloadable kit with recommendations for plan development, submittal, and implementation, best practices, and additional resources. While some of these materials are California-specific, many are complementary for CWPP development across the U.S.

Recent publications

Going Slow to Go Fast: Landscape Designs to Achieve Multiple Benefits evaluates the compatibility of treatments for (short-term) fire risk reduction and (longer-term) ecosystem resilience. This paper from the Pacific Southwest and Rocky Mountain Research Stations finds that short-term fire risk reduction and long-term resilience objectives can be complementary within a landscape, but ecosystem resilience is not a guaranteed co-benefit when fire risk reduction is the primary objective. Rather, improving ecosystem resilience cannot be achieved quickly because many desired forest conditions require both deliberate strategic action to guide the location, character, and timing of management as a disturbance agent, as well as adequate time for landscape conditions to improve and resilience benefits to be realized. Sometimes, implementation of mitigation measures for fire risk reduction can be out of alignment with actions necessary to achieve holistic ecosystem health and long-term resilience. The article also offers recommendations to meet multiple objectives.