Happy Wednesday, Fire Adapted Community!

How do we measure the cost of a wildfire? The financial burden of suppression and containment efforts is one metric which is documented fairly consistently at the national level; however, this doesn’t account for the broader range of expenses such as property damages, public health impacts, and long-term economic, social, and environmental impacts. A 2013 study out of New Mexico found that the full cost of wildfires far exceeds suppression, that costs vary significantly from fire to fire, and that direct and indirect costs are incurred first by individuals and private businesses and then by federal, state, and local governments. Today’s newsletter dives into full cost accounting of wildfires, a perspective shift which can help to highlight the financial, as well as ecological, importance of fire prevention and resilience work.

This Wildfire Wednesday features:

FCA in New Mexico and the Southwest - case studies and lessons learned

Job Opportunities

Fire Planning Task Force Updates

Reserved Treaty Rights Lands Program: The Power of Partnership

Treatment and Wildfire Interagency Geodatabase (TWIG)

Have a wonderful end to your November,

Rachel

What is full cost accounting?

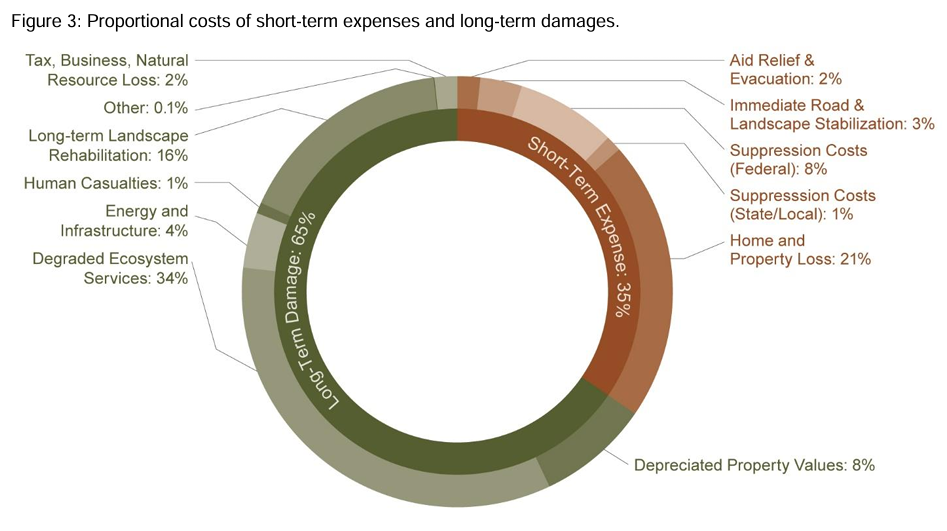

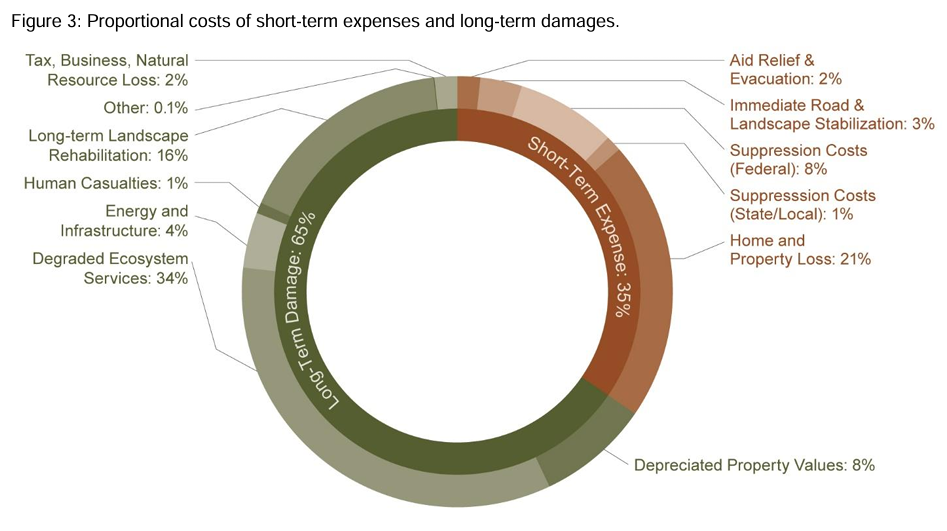

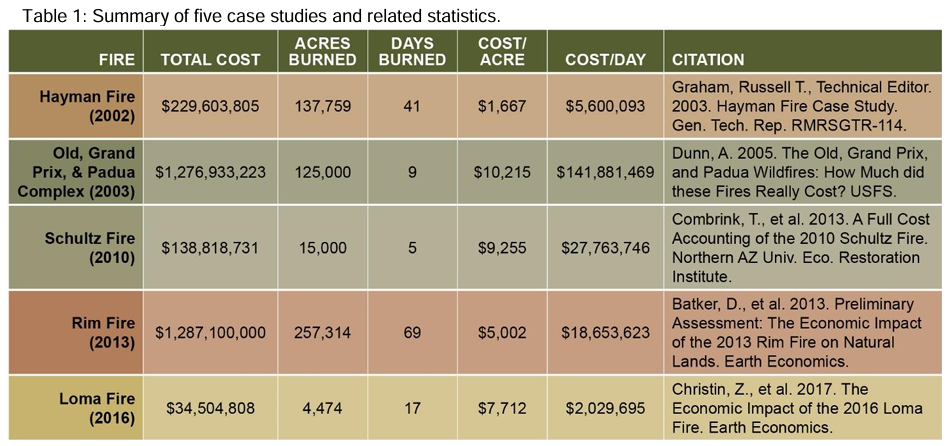

“Wildfire costs greatly vary depending on factors within the built and unbuilt environment. Socioeconomic context, housing density, the duration and size of a wildfire, and other variables influence the overall cost. In general, upward trends in urban growth and development in areas at risk to wildfires suggest a parallel rise in total wildfire costs.” On average (nationally), suppression costs comprise only about 9% of total wildfire costs, and “almost half of all wildfire costs are paid for at the local level, including homeowners, businesses, and government agencies. Many local wildfire costs are due to long-term damages to community and environmental services, such as landscape rehabilitation, lost business and tax revenues, and property and infrastructure repairs” (Headwaters Economics, 2018) and other unexpected impacts such as declining property values after a fire, harm to health, and changes to ecosystem processes. The economic impacts of wildfire can permeate and accrue for years to decades. Full cost accounting takes all of these fiscal impacts into consideration to reach a more holistic estimate of the cost of wildfire.

“Full cost accounting after wildfires is critical for adequate government budgeting, post-wildfire resource allocation such as disaster recovery assistance and understanding the full scope of wildfire to help communities learn to better live with fire” (Hjerpe et el., 2023). For a good overview of the complexity of full cost accounting, view this blog from the Council of Western State Foresters.

How is full cost accounting measured?

Full cost accounting is dependent on a number of highly nuanced factors. The Full Cost of New Mexico Wildfires mentions that:

Costs depend on the location of the wildfire as well as the severity and length. For example, a wildfire occurring near a heavily populated area may result in significant evacuation costs through displacement of residents and businesses, and smoke-related illnesses will likely be greater. In contrast, a wildfire occurring in a remote area may incur more costs through impacts to wildlife habitats, watershed and water supplies, or recreation areas.

Costs are incurred initially and over succeeding years - there is a temporal dimension to wildfire costs. Many costs are incurred during or immediately after the fire and their impacts are relatively temporary (e.g. suppression, evacuation, disruption of tourism and transportation routes) while others (e.g. impacts to respiratory health and water sources and destruction of habitat, timber resources, residential and commercial structures, and watershed areas) may occur concurrent with the wildfire but the rehabilitation, rebuilding, and repair will take much longer.

In the arid American West, long-term damage to forest watershed resources (such as damaged water supply infrastructure and post-wildfire flooding) may represent the largest, and least documented, costs of uncharacteristic wildfire over time (Lynch, 2004).

The burden of costs varies - just as the magnitude and type of cost is case-specific for each wildfire, the distribution of who absorbs these costs is different for each incident.

The Western Forestry Leadership Coalition published a 2022 report which breaks costs down into three categories -

Those costs which occur as a result of a wildfire:

Direct Costs, which are incurred directly during an incident.

Indirect Costs — losses which are incurred after an incident but are attributable to it.

And those which represent expenditures that would reduce the incidence of and damage from future catastrophic fire:

3. Indirect Costs — mitigation Investments.

FCA in New Mexico and the Southwest

While there are examples of full cost accounting for fires in the West (see “Case Studies”, pages 7-16), the practice is still comparatively rare because of the difficulty obtaining the relevant data. A recent remeasure of the full cost of the 2010 Schultz Fire in Arizona, while illuminating the longevity of post-fire impacts and expenses, was still conservative as it did not account for every potential direct and indirect ‘net value change’ (e.g. non-mortality related impacts to physical and mental health).

This remeasure found that 10 years post-fire, total accrued wildfire costs were 29–35% higher than the initial full cost accounting performed in 2013, bringing the current-day cost for this 15,000-acre fire to ~$180.4 million. The authors write “given the trends of increasing wildfire severity and duration of fire seasons, combined with… myriad costs of wildfire, it is safe to assume the full costs of wildfire are vastly underrepresented and enormous. Additionally, as the Schultz Fire example demonstrates, a single fire often has many costs that are difficult to quantify and are temporally dispersed, such as costs to ecosystem services or community well-being. This further emphasizes the importance of proactive fuel treatments and forest restoration work to reduce the risk of uncharacteristic fire and restore ecosystem health… Millions of dollars may have been saved by forest restoration treatments in key parts of the Schultz Fire perimeter before the fire.”

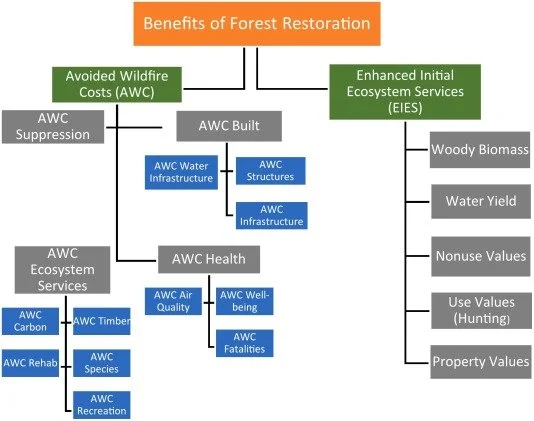

One key to understanding the full cost of wildfires is recognizing that these climbing costs and consequences are linked to increasingly uncharacteristic fire behavior and impacts driven by changes to our climate and ecosystem conditions. In these southwestern fire adapted landscapes, wildfires can also result in ecological benefits, especially in the areas that do not burn at high severity and are long overdue for fire. It is when fires burn hot and large enough to cause severe impacts to ecosystem functions and communities that the damages really begin to accrue. Forest restoration treatments result in overall lower-severity fires, which lessens the intensity of subsequent impacts, including post-wildfire flooding; “in the most valuable and at-risk watersheds, every dollar invested in forest restoration can provide up to seven dollars of return in the form of benefits and provide a return-on-investment of 600%” (Hjerpe, 2024).

Investing in prevention of human-caused ignitions and emerging wildfire detection tools and technology are also promising financially prudent measures to avoid or reduce the full cost of wildfires. These approaches can decrease the number of wildfires which burn into communities and devastate landscapes - especially during times of the year when wildfires are more prone to rapid spread and growth in intensity due to weather, wind, and availability of fuel. Remote sensing enables the early identification and tracking of wildfires over large geographic areas, providing valuable information for engagement, decision-making, and fire resources allocation. Decision-support data products may have a large impact in some situations (e.g., an extreme day with multiple ignitions, a fire threatening a high value asset, etc.), and a limited impact in others (e.g., wet fire seasons, fire activity beyond the capacity of suppression resources, etc.). Preventing or mitigating one future extreme event may economically justify these tools many times over (Hope et al., 2024). While the cost of operating fire detection tools (towers, cameras, etc.) exceeds their value in the reduction of direct suppression costs, the benefits are realized in the reduction of total wildfire costs. Further research on the cost-benefit ratio of these tools is needed as current analyses are limited.

Upcoming Opportunities and Additional Resources

Job Opportunities

Community Wildfire Defense Grant (CWDG) Manager with NM Forestry Division

New Mexico Forestry Division is currently hiring for a Community Wildfire Defense Grant (CWDG) Manager. The position application will be open through December 5, 2025.

This position will manage the state's Community Wildfire Defense Grant program. The position responsibilities are to manage, direct, and actively engages in forest and watershed management and community wildfire risk reduction within the Forestry Division's jurisdiction of 43 million acres of state and non-municipal private land. The position is responsible for ensuring the eligible local governments, Tribes and non-governmental organizations receive funding for Community Wildfire Protection Planning (CWPP) and implementation of wildfire mitigation projects described in CWPP.

For questions about the position, please reach out to Melissa McLamb, (505) 394-2277, (Melissa.McLamb@emnrd.nm.gov).

Fire Planning Task Force Updates

November 2025 Public Meeting Minutes

On November 17th, 2025, the NM Fire Planning Task Force convened to review recommendations from the CWPP Sub-group, hear updates from both the Mapping and Standards Sub-group, hear a report on F.A.I.R Insured Home Hardening Grants, and more.

The attached minutes provide more details on all agenda items including:

Outcomes from the review of CWPPs from Eddy County, Sandavol County, and Eldorado Communities

Adoption of the IBHS Wildfire prepared Home standards as voluntary standards for home hardening and mitigation in New Mexico

Pilot of the Office of the Superintendent of Insurance’s Home Hardening grant in Wimsatt, New Mexico

Reserved Treaty Rights Lands Program: The Power of Partnership

The Nature Conservancy in Montana produced a short video, “Reserved Treaty Rights Lands Program: The Power of Partnership,” which looks at how the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes are working with the Bureau of Land Management and The Nature Conservancy to conduct burns on off-reservation lands with Tribal treaty rights in a unique partnership made possible by the Reserved Treaty Rights Lands (RTRL) program. The RTRL program, which is administered by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, provides funds to protect and enhance natural and cultural resources on Tribes’ aboriginal lands that are at high risk of wildfire.

Treatment and Wildfire Interagency Geodatabase (TWIG)

The Southwest Ecological Restoration Institutes (SWERI) have launched the 1.0 version of their free tool, the Treatment and Wildfire Interagency Geodatabase (TWIG), a collaborative, open-access data platform that makes national fuel treatment and wildfire information accessible to all.

As a national, open-access geodatabase, TWIG centralizes federal treatment and wildfire data in one publicly available platform. By doing so, it:

• Empowers communities and land managers to demonstrate the effectiveness of fuel treatments

• Helps researchers and policymakers understand treatment-wildfire interactions at landscape and local scales

• Promotes cross-agency coordination and transparency in wildfire risk reduction efforts