Historically, most wildfires in the United States occurred between May and November with peak fire season happening in August when conditions are hottest and driest. However, as weather patterns change, temperatures rise, drought events increase, and pests, disease, and invasive species make forests more vulnerable, wildfires outside of the traditional fire season have become more common over the past two decades. Since 2017, some of the most destructive fires in the western U.S. have burned outside of that typical fire season (Thomas Fire, CA; Marshall Fire, CO; Smokehouse Creek Fire, TX; Palisades/Eaton Fires, CA). Many of these have been fueled by unseasonable or long-lasting (and often record-breaking) heat and strong winds, causing explosive fire growth. Recovery from these fires takes years to decades and the landscape, and the communities impacted, will be permanently changed.

As we approach the one year anniversary of the LA conflagrations (the Palisades and Eaton Fires) and consider the changing reality of large destructive fire events, the question becomes what we can learn from past fires - how they burned, how fire personnel and emergency managers responded, how communities faired, and how we have or have not been able to recover - to inform and improve how we live with and prepare for fire in the future.

This Wildfire Wednesday features:

Lessons from the LA conflagrations and other unseasonable fires

Have a peaceful and restful end to your year,

Rachel

Lessons from recent large urban conflagrations

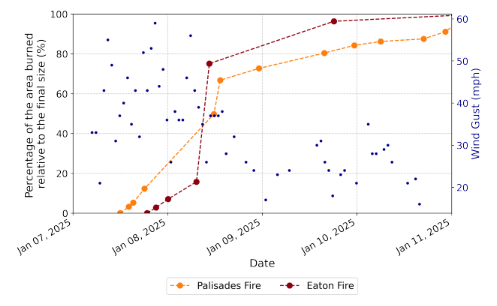

One key aspect of what made the 2025 LA urban conflagrations - the Palisades and Eaton Fires - so intense is that they burned under red flag conditions (strong winds, low relative humidity, and dry fuels) which indicate an increased potential for extreme fire behavior and rapid fire growth. During the first five hours following ignitions, these fires were burning under environmental conditions which exceeded the extreme fire behavior thresholds of 2-minute sustained wind speeds exceeding 20 mph, peak 5-second gusts exceeding 30 mph, and relative humidity below 15%. These conditions meant that vegetation was dry and ready to burn and very high winds pushed the fires further and faster than firefighters could respond.

Anne Cope, an Institute for Business and Home Safety staffer who helped write the findings report on the LA Conflagrations, notes that “each wildfire event reminds us communities must prepare for the few days a year of dry hot winds — not the calm of everyday life. When fires ignite on the worst days, these winds push embers, flames and heat into entire neighborhoods. But the science is clear – when communities work together, we can disrupt the path of conflagration.” Below are some key takeaways from that report which may inform or reinforce our preparedness priorities and actions.

Individual preparedness

Nearly all aspects of the potential for structure ignition fall into two primary categories: the building materials used to construct the exterior of the structure and the intensity of fire exposure from the surrounding environment. The latter is closely correlated with connective fuels and the distance to surrounding fuel (e.g., decks, shrubs, sheds, or structures). (pg. 18)

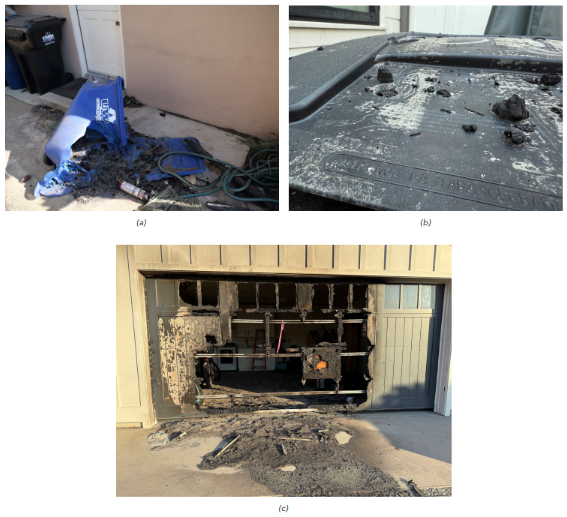

When connective fuels allow the fire into close proximity of the structure, vulnerable components - windows, decks, and open eaves - provide the initial ignition points that determine a structure’s outcome. (pg. 57)

Mitigation only works as a system, and partially executed mitigation strategies allow fire pathways and vulnerabilities to persist. Most homes exposed in the Palisades and Eaton Fires featured at least one resilient component, with noncombustible siding and Class A roofs being the most common (enhanced resistance to radiant heat and direct flame contact) and ember-resistant mesh screens on vents being the least (left these openings vulnerable to ember exposure). Many structures also had inconsistent resilience in different parts of their Zone 0 (e.g. a noncombustible pathway around three sides with vegetation and flammable furniture on the fourth side) which increased their vulnerability to near-structure flame exposure. These partial resilience improvements left major vulnerabilities, highlighting that resilience must be evaluated as a system of building components and defensible space. A structure is only as resilient as its weakest component. (pg. 45)

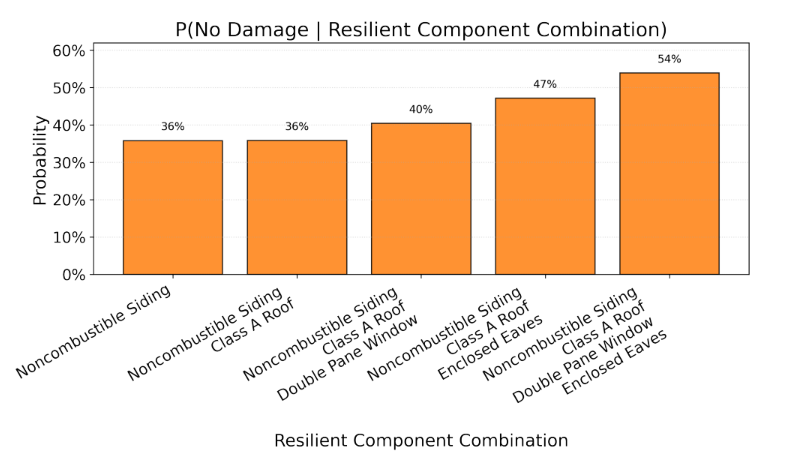

As the number of resilient components increases (e.g. noncombustible siding, Class A roof, double-pane windows, and enclosed eaves) the probability of experiencing no damage increases from 36% to 54%, demonstrating effectiveness of using systems-based home-hardening. These findings underscore the importance of establishing minimum performance requirements through parcel-level building codes.

This parcel-level approach is especially important in typical suburban neighborhoods, where maintaining more than 30 ft of separation between structures is often not feasible. Where structural density cannot be reduced in suburban environments, the building materials and connective fuels—especially those closest to the structure—become even more important. (pg. 4)

The zone immediately surrounding the home (Zone 0) is the most impactful place to make improvements.

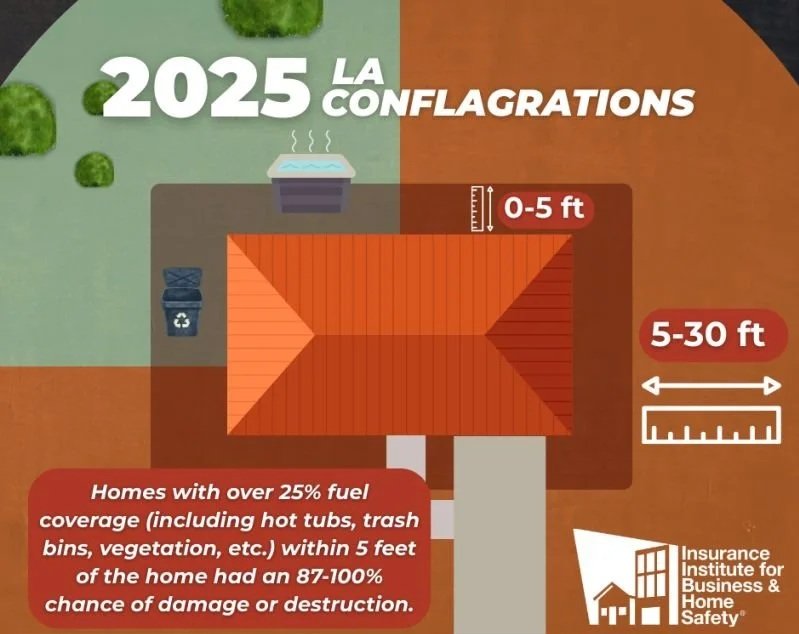

Some types of fuel commonly observed within Zone 0 can unexpectedly threaten structures under extreme fire conditions. In the communities impacted by the Eaton and Palisades Fires, trash bins, hot tubs, furniture, vegetation, and more within 5 feet of homes created ignition pathways (bins caught fire which then ignited the adjacent structure) and caused damage. In these cases, the primary combustible component was not the plastic bin itself but rather its contents inside. (pg. 32)

No plant, regardless of its flammability rating, is fireproof, and even well-maintained, well-hydrated vegetation can be rapidly dried to the point of ignition due to the intensity and duration of fire exposure during the extreme fire behavior scenarios of a conflagration. This burning vegetation close to homes can then compromise the building’s integrity when combined with other forms of exposure. (pg. 30)

Many studies have shown that fences built out of combustible materials, such as wood or latillas, can enable fire to move through communities; the use of noncombustible fences (e.g. metal or chainlink) reduces the potential for fire spread, particularly for fences that touch the home. However, in LA vegetation that caught fire was observed growing up or through noncombustible fences, reducing or eliminating the resilient effect of the noncombustible fence material. (pg. 35)

Even if homeowners reduce fuels in the zone that is 5-30 feet away from the home (Zone 1), structures with dense fuel coverage - greater than 25% - in Zone 0 are almost guaranteed to sustain damage or destruction (probabilities exceeding 87%). Overall, reducing fuel coverage both in Zone 0 and Zone 1 to less than 25% produces a meaningful reduction in the probability of damage or destruction to structures. (pg. 55)

Resilient building components offer limited benefit when heavy fuel loads remain close to the structure. (pg. 57)

Community preparedness

Firefighter effectiveness is strongly impacted by community design. (pg. 26)

Neighborhoods with high structure density and limited separation distances are likely to experience multiple near-simultaneous ignitions, quickly overwhelming suppression capacity. Communities with tight structure spacing and dense connective fuels have amplified fire risk exposures between homes and reduced effectiveness of defensive actions (fire suppression and structure protection).

The presence of defensible space increases the effectiveness of defensive actions (e.g. during the Eaton Fire, homes threatened in Kinneloa Mesa were reported to have good defensible space, which allowed Los Angeles County Firefighters to effectively defend them).

While parcel-level mitigation is necessary, it is not always sufficient to prevent large-scale loss, particularly under extreme fire weather conditions or in densely built neighborhoods. Post-conflagration studies have shown that structure separation, connective fuels, and building materials are the three central pillars of risk, with structure separation and connective fuels controlling the intensity of heat exposure and building materials defining a structure’s capacity to resist it. (pg. 51)

Even structures with 4 resilient building component characteristics but which have less than 10 ft of separation have a greater than 50% chance of being damaged. When the space between structures is less than 10 ft, the likelihood that a fire will exploit the weakest link in a structure greatly increases, often overwhelming the protective benefits of one or two resilient building features. At such tight spacing, if one building ignites, it is almost certain that wind driven flames will extend the full 10 ft downwind to touch the adjacent structure. (pg. 53)

When structure spacing is greater than 30 ft, the probability of no damage increases to 66% with those same 4 resilient building component characteristics. Adding either enclosed eaves or double pane windows to the resilient system (on top of noncombustible siding and a Class A roof) increases the probability of no damage.

Houses oriented downwind of the fire were consistently damaged or destroyed at higher rates than structures in crosswind or upwind exposures (due to diminished intensity of heat transfer in the upwind and crosswind directions); however, structures at all wind exposure orientations remain highly vulnerable when spacing between structures is minimal. (pg. 51)

Overall takeaways

Parcel-level resilience must be applied as a comprehensive system and paired with reductions in connective fuels at the neighborhood scale to meaningfully limit structure loss during wind-driven built-environment conflagrations. (pg. 58) To reduce overall suburban conflagration risk, parcel-level measures must be complemented by community-level actions—particularly efforts to reduce structural density and connective fuels. (pg. 4)

In urban conflagrations, damage is driven by the intensity of the fire, driving conditions (e.g. strong winds), and the fire’s ability to access an ignition pathway from one structure to another. These ignition pathways are created through either localized flame exposures that exceed the tolerance of building materials or through ember intrusion into unmitigated openings.

A systems-based approach that combines resilient construction, strategic fuel management, and community-wide mitigation is essential for wildfire resilience.

Spacing between structures (homes) and connective fuels, combined with environmental factors like wind speed and direction, are the two biggest driving factors which determine whether fire moves between homes, becoming a conflagration, or where structures are defensible.

When creating separation between structures isn’t possible, homeowners must take key steps. When homes featured 4 hardened components – a Class A roof, noncombustible siding, double-pane windows and enclosed eaves – the likelihood of avoiding wildfire damage was 54%, regardless of how close homes were to one another.

Homes with fuel covering more than 25% of Zone 0 faced an 87-100% chance of damage or destruction. That includes trash cans, patio furniture, and shrubs.

Upcoming Opportunities and Additional Resources

East Mountains Town Hall - January 12, 5PM

Los Vecinos Community Center

Ruidoso Town Hall -

January 15, 5PM

Ruidoso Convention Center

Join PNM at an upcoming community event focused on wildfire safety and learning more about their Public Safety Power Shutoff (PSPS) process. These gatherings are designed to share critical information, local resources, and practical tips to help protect your home and neighborhood.

PNM Public Safety Power Shutoff (PSPS) map of high fire risk areas that may experience a PSPS.

National Forest Foundation - Matching Awards Program (MAP): Connecting People to Forests

January 22, 2026: Deadline for Round 1 2026 MAP Applications

MAP funds projects that inspire participants to be personally involved in caring for their public lands. NFF requires that all MAP projects include three elements: community engagement, hands-on stewardship activities completed by the engaged community members, and a direct benefit to the National Forest System. Nonprofit organizations, Tribal governments and organizations, and universities are eligible to receive MAP grants.

Rocky Mountain Research Station - Science You Can Use in 5 minutes

Trees in Distress: Prefire drought increases postfire mortality

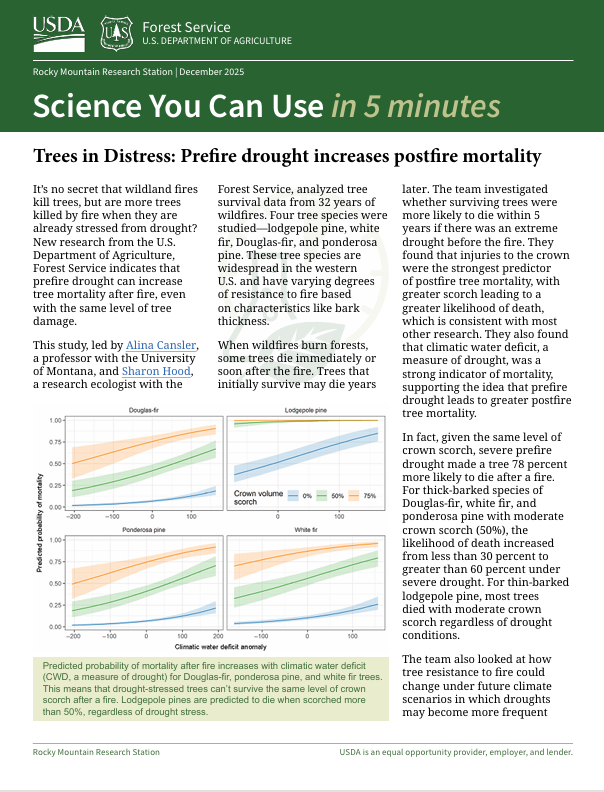

Looking at four tree species—lodgepole pine, white fir, Douglas-fir, and ponderosa pine—a study led by a professor with the University of Montana and a research ecologist with the Forest Service investigated whether surviving trees were more likely to die within 5 years of a fire if there was an extreme drought before the fire. They found given the same level of crown scorch, severe prefire drought made a tree 78 percent more likely to die after a fire. Therefore, into the future, western forests that have thick barked tree species may become less resilient to fire because of increasing drought stress.

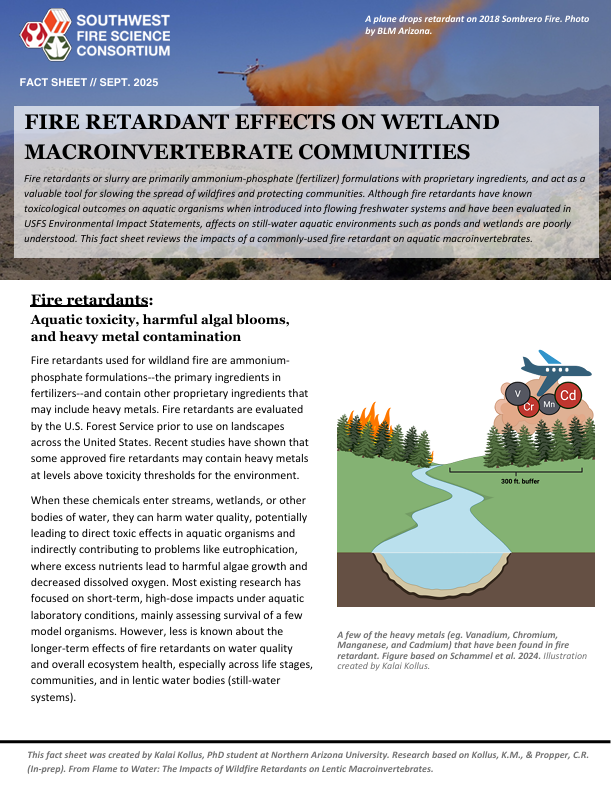

The Southwest Fire Science Consortium released a fact sheet that discusses a review of the impacts of a commonly used fire retardant on aquatic macroinvertebrates. The main takeaway from the research highlighted in the fact sheet is fire retardants can seriously affect aquatic life and may contribute to water quality problems, especially in wetlands and ponds where the water is stagnant and exposure may be prolonged. Researchers also highlight that proactive fuel reduction and prescribed fire—especially near water sources and communities—can reduce unplanned fire risk and the need for chemical fire retardants.