Hello Wildfire Wednesday readers,

Happy Valentine’s Day!

Today, we’re going to get extra romantic and talk about a critical and evolving aspect of hazardous fuels reduction—disposal of slash and leftover small diameter woody material. This has traditionally been viewed as a waste product due to its minimal value in commercial markets and is usually disposed of by piling and burning or scattering or chipping and leaving onsite to decompose. Alternative methods to utilize these materials are gaining momentum as new products are developed and marketed, presenting exciting opportunities for increased revenue for landowners, job creation, and benefits to the environment, our forested landscapes, and the soil. There are opportunities to partake at both the landscape and individual scale, with accessible technologies such as backyard biochar production. The alternatives outlined below can help reshape the ways we approach slash disposal as communities and organic yard waste disposal as residents.

This Wildfire Wednesday features:

A definition of Biomass Utilization and program examples at the landscape scale.

Upcoming events, funding opportunities, and additional resources.

In-person learning exchange: Bernalillo County Pile Burn Workshop

Funding opportunities: slip-on tankers and FACNM Microgrants

Other resources, including a free biochar workbook.

Read on!

-Dayl

What is Biomass Utilization?

Biomass utilization refers to the conversion of recently harvested organic materials into energy or various bio-based products. Biomass can include a wide range of materials such as wood, crop residues, and agricultural by-products. The goal of biomass utilization is to create value-added products for wide-ranging applications or harness the energy stored in these organic materials.

There are many ways in which biomass can be utilized:

Bioenergy production: Biomass can be used to generate heat, electricity, or biofuels. Common processes for bioenergy production include combustion, gasification, and fermentation.

Bioproducts: Biomass can be processed to extract valuable bioproducts such as building materials and biofuels. Some unique examples of bioproducts include Woodstraw for erosion control and Wood Wool Cement board for construction.

Biochar production: Biomass pyrolysis can produce biochar, a carbon-rich material that can be applied to soil to improve fertility, carbon sequestration, and overall soil health. Mobile technologies such as the air curtain burner may allow for biochar production directly within a forest treatment worksite (as opposed to hauling biomass offsite for biochar production).

Anaerobic digestion: Organic waste and biomass can undergo anaerobic digestion, a biological process that produces biogas (methane and carbon dioxide) as a renewable energy source and also generates digestate, a nutrient-rich fertilizer.

Co-firing: Biomass can be co-fired with coal in power plants to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and transition towards cleaner energy sources.

These technologies present a new opportunity to close the loop in hazardous fuels reduction and augment traditional methods such as pile burning, which can impact air quality with emissions, and onsite decomposition, which fails to fully reduce fire risk by leaving the hazardous fuels in place. Leveraging woody biomass sourced from public lands has the potential to not only reduce carbon dioxide emissions but also to grow rural economies. The biomass that is created through hazardous fuel treatments can be extracted and repurposed for bioenergy and bioproducts, offering a sustainable and multifaceted solution.

It’s not as simple as just implementing these new strategies, however. The forest products industry faces significant challenges in implementing large-scale forest restoration projects due to constraints including limited capacity, regulatory barriers, disruptions in supply chains, workforce shortages, logistics hurdles, and a lack of viable markets. One response to these barriers is the Wood Innovations Grant established by the Forest Service to facilitate the expansion of wood and biomass utilization.

Examples of Biomass Utilization in Action

SWERI Wood Utilization Team

With the support of a Wood Innovations Grant, the Wood Innovations and Utilization Team at the Southwest Ecological Restoration Institutes (SWERI) was born. The objective of the project is to establish a center of expertise and provide crucial support for the development of forest-based enterprises. These interconnected operations will generate markets that support the restoration of forests and grasslands in the Southwest, create jobs and expand rural economies, and align with watershed protection and fire prevention. Read more in this article from Northern Arizona University.

Placer County, California - Forest Biomass Removal on National Forest Lands

Placer County is exploring and prioritizing projects that collect, process, transport, and utilize woody forest biomass wastes for renewable energy as an alternative to pile burning or mastication. In a public-private partnership demonstration project (report (PDF)/video), over 6,000 tons of slash from fuel hazard reduction treatments in the Tahoe National Forest were utilized for energy. In addition, the state of California Forest Biomass to Carbon-Negative Biofuels Pilot Program funded six projects that demonstrate technologies and plans for the creation of energy from local forest biomass.

What is Biochar?

Biochar is a type of charcoal that is created through the pyrolysis process, which involves burning organic material derived from agriculture, forestry, or - on a smaller scale - yard waste. This process occurs in a container with very low levels of oxygen, resulting in minimal smoke and volatiles emissions. You may have already made biochar on your own - perhaps when extinguishing a campfire or a woodstove at the end of a night by dousing it with water or smothering it with dirt - without even knowing it! The natural charcoal that results is the same material as biochar.

Biochar is very useful as a soil amendment, enhancing water and nutrient retention and attracting beneficial microbes via its incredible porosity and negative surface charge. Beyond its soil-enhancing properties, biochar serves as an effective method for sequestering carbon in the soil and preventing it from entering the atmosphere. Typically, the decomposition of organic matter emits greenhouse gases such as CO2 and methane. However, through pyrolysis, the carbon in organic matter is locked into a decay-resistant form, effectively sequestering it indefinitely.

How to make biochar in your backyard

Making biochar in your backyard is a relatively simple process that can be accomplished with basic materials. Here's a step-by-step guide.

(You can also find a cornucopia of resources and instructional videos by doing a quick online search. Each method is going to vary slightly from the next, showing that there are many “correct” ways of making biochar!)

What you’ll need:

Metal barrel or in-ground open pit: You'll need a metal container with air holes punched in the bottom or a cone-shaped pit dug into the ground. The air holes in the bottom of your metal barrel will pull air up from the narrow point in the bottom of the hole, removing oxygen from the feedstock. The conical shape of the pit will do the same (it should be about as deep as it is wide). The Quivira Coalition offers biochar kiln loans to support people doing their own land stewardship!

Starting material: Dry wood, paper, or other fine woody debris can be used to start the combustion process. Dry tumbleweeds are an effective and satisfying starter. These materials will be layered on top of the pile that you are burning.

Biomass feedstock: Collect woody biomass, such as branches, twigs, or pruned tree limbs to build your pile, and keep some finer materials aside to continually feed the fire once pyrolysis has begun.

Safety gear: Protect yourself by wearing gloves, pants, and long sleeves and have plenty of water onsite in case anything gets out of hand.

Steps to make backyard biochar:

Gather and load biomass:

Fill the barrel or fire pit with the dry woody material, making sure not to overfill it. Put fine fuels (kindling) on top of the pile in a dense, thick layer.

Four pounds of biomass can make close to one pound of biochar, depending on materials and the efficiency of the burn.

Ignition:

Using your preferred lighting technique, start burning the pile by igniting the kindling layer on top of your feedstock. A propane torch is the easiest way to evenly light the kindling layer.

As the kindling is consumed, continue to add more kindling on top. This will keep air moving upwards and encourage the feedstock layer below to catch fire.

Pyrolysis process:

As the biomass undergoes pyrolysis, it will release gases and leave behind biochar.

Keep adding more kindling materials on top as it burns down. The purpose of this is to keep the fire on top of the feedstock to burn away the smoke as it comes off.

The flame will be mostly yellow as it consumes gases, and little to no smoke will be produced.

Monitoring:

Keep an eye on the process to ensure that the biochar doesn't turn into ash due to excessive oxygen. Once you see ash starting to form, start layering more biomass on top in an even layer to keep oxygen levels low.

If you see lots of smoke forming, you may be adding too much material too fast.

Quenching:

When all of your feedstock has turned into a pile of red-hot coals, it is time to quench the fire!

Using a hose, thoroughly douse the coal bed. Rake the wet coals to find hot spots and re-wet as needed until it’s cold.

You can also quench the fire by piling a layer of soil on top. This will stop the flow of oxygen and prevent your feedstock from turning to ash.

Collecting biochar:

After a day or two of cooling and drying out, carefully collect the biochar. The biochar should be brittle and crumble easily in your hands.

Crushing or grinding (optional):

If desired, crush or grind the biochar to achieve a more uniform particle size. This can enhance its effectiveness when incorporated into the soil.

Incorporating into soil/compost:

Incorporating biochar into a compost pile first can be beneficial, as this will “charge” the micropores of the biochar with nutrients.

Incorporate the biochar compost mix into your garden soil at a recommended ratio of around 5-10%.

*Remember to conduct biochar production in a well-ventilated outdoor area, away from flammable materials, and be cautious about fire safety! Additionally, be aware of local burning and air quality regulations.*

Additional Resources, Events, and Funding

Webinars

February 20, 2024 at 12pm: Post-Wildfire Recovery Through The Principles of Engineering with Nature

Hosted by the Southwest Fire Science Consortium and co-hosted by the Arizona Wildfire Initiative.

Following a severe wildfire, recovery efforts can benefit from using “Engineering With Nature” principles to utilize existing materials on the landscape for slope stabilization, erosion control, and stream restoration. Join presenter Chris Haring of the USACE-Engineering Research and Development Center to learn about the successes and lessons learned with these techniques in Santa Clara Canyon, NM after the destructive Las Conchas Fire.

February 23, 2024, 12:00 - 1:30 pm: Lunch and Learn - Wildland Fire Mitigation and Management Commission

Hosted by the Forest Stewards Guild.

This special Lunch and Learn webinar will cover the 2023 Wildland Fire Mitigation and Management Commission report. Presenter Neil Chapman, Wildland Fire Captain with the Flagstaff Fire Department and Commission member, will discuss the 2021 creation of the 50-member Commission, its mission to recommend improvements to how federal agencies manage wildfire across the landscape, and the recommendation creation process, outcomes, and next steps following publication of the Commission's report.

Learn more and read the report with its 148 final recommendations.

In-Person Learning Exchange

Saturday, February 24 from 10am - 2pm: Bernalillo County Pile Burn Workshop

This Bernalillo County workshop for forest and fire practitioners and interested landowners will cover a variety of topics related to pile burning, such as writing prescriptions, pile construction, PPE, containment, and permitting. The workshop will include both classroom and field components and will introduce attendees to the State's Certified Burn Manager Program. Lunch will be provided to participants and registration is required.

Agenda:

10:00am – Classroom: State burner program, prescriptions, permitting

12:00pm – Field: Pile construction, containment, PPE

2:00pm – Wrap up

Funding Opportunities

FACNM Microgrant Opportunity to fund your community fire preparedness event: FACNM Leaders and Members are eligible to apply for grants awards of up to $2,000 to provide financial assistance for:

Convening wildfire preparedness events,

Enabling on-the-ground community fire risk mitigation work, or

Developing grant proposals for the sustainable longevity of their Fire Adapted Community endeavor.

Round 2 is open through February 28, 2024.

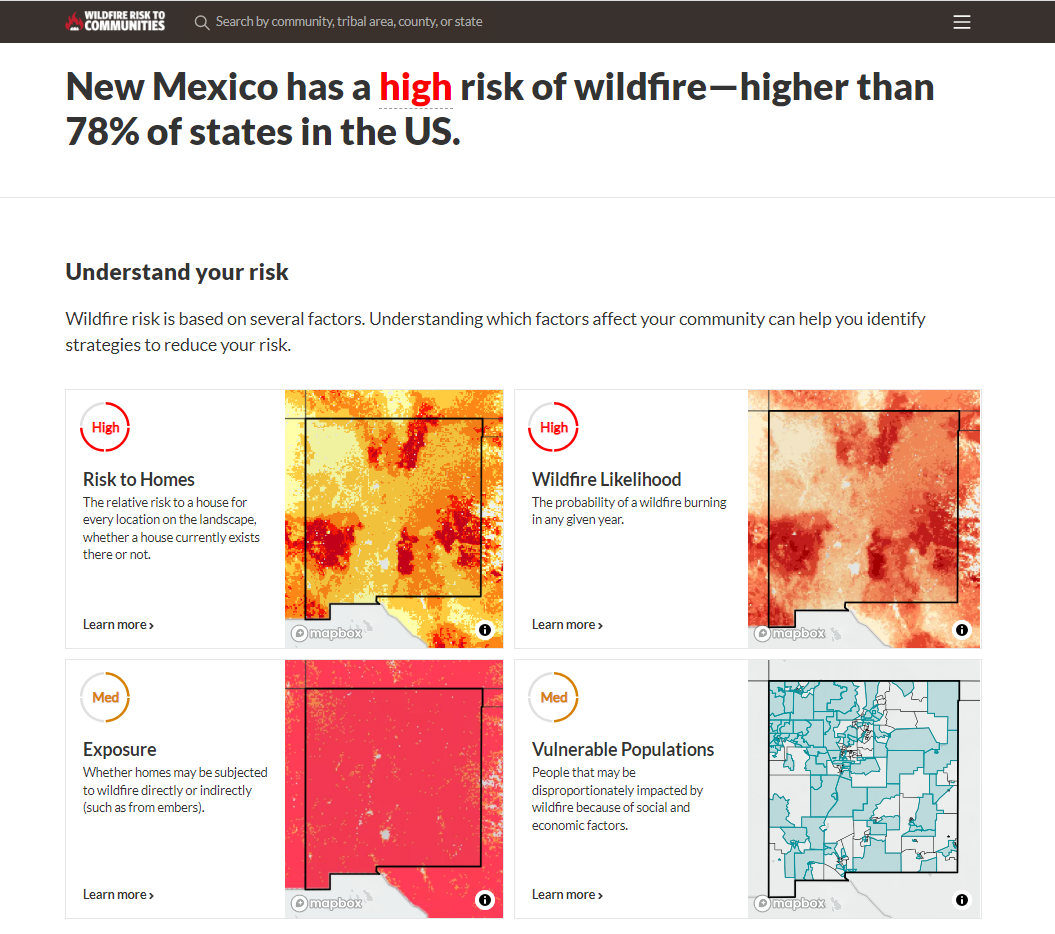

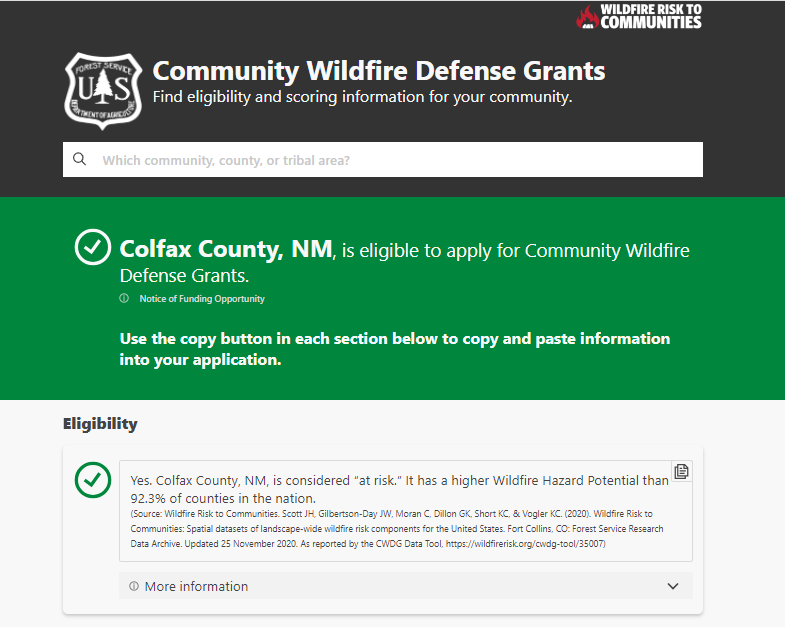

Grant Opportunity for Slip-on Tanker Units: This new pilot program from the Department of the Interior will fund local governments to purchase slip-on tanker units, allowing them to quickly convert trucks and other vehicles for operation as wildland fire engines. Governments that provide emergency services to areas with a population of 25,000 or less are eligible to apply and grant amounts will range from $10,000 to $200,000. A new search tool allows communities to determine their eligibility for this program.

Statements of interest are due March 21.

Additional Resources

Biochar in the Southwest: Using New Mexico Practices and Regulations as a Model

CJ Ames and Eva Stricker, PhD, Quivira Coalition and Kelpie Wilson, Wilson Biochar Associates

This workbook from the Quivira Coalition offers practices on New Mexico lands as a model for making and using biochar in a relatively hot, dry, and windy environment. It is both a primer on what biochar is and what makes it a useful tool in land management, as well as a guide on how to produce and distribute it on the land. This workbook is intended to accompany in-field or video training that will enable land stewards and technical service providers to safely produce biochar for use in their operations.

Read the free online version! Hard copies are available for purchase from the Quivira Coalition Store.

Forest Resource Index for Decisions in Adaptation (FRIDA): A library of climate adaptation support tools for forest management.

The Forest Resource Index for Decisions in Adaptation (FRIDA) is a library of climate adaptation support tools for forest stewardship in the Southwest.

FRIDA is an online library of decision-support tools and resources to help support climate change adaptation decision-making and forest stewardship in the Southwest. FRIDA allows managers and decision-makers to easily query based on their objectives and area(s) of interest. Users can filter resources by topic, region/state, resource platform, and vegetation type to efficiently find the most relevant region-specific tools and resources to best fit their needs.