Happy Wildfire Wednesday, FACNM readers!

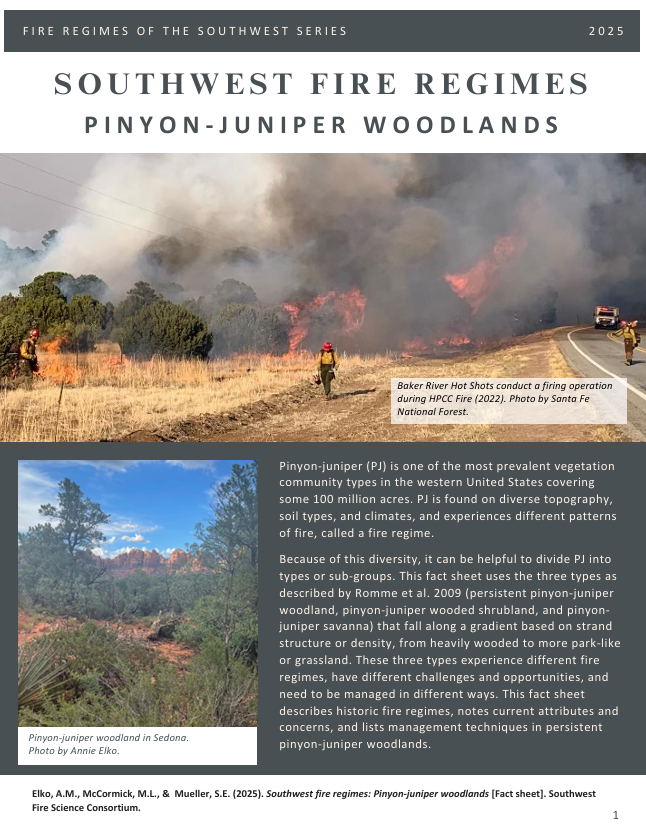

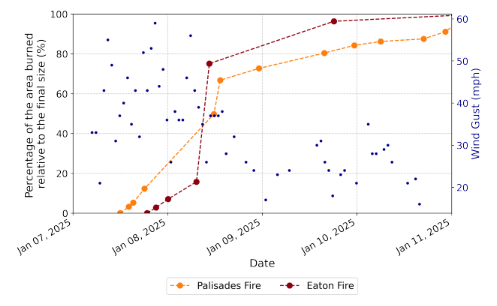

New Mexico’s spring wildfire season kicked off last week with the 2,670-acre 352 Fire in the eastern plains near Tucumcari, quickly followed by the Brockman and Smith Fires in eastern NM. There are other large fires burning in the Oklahoma and Texas panhandles; what they have in common is that they are burning through grasslands and prairies and are largely driven by these spring winds, causing very fast-moving fires through hot flashy fuels. As Nico Porcelli (National Weather Service) told KRQE News, “we’re kind of in the thick of it right now. We’ve already been seeing strong wind gusts between 50 and 70 miles per hour, mainly along and east of the central mountain chain.”

Still shot taken on the day of newsletter publication of several news articles on grassland fires in the southwest.

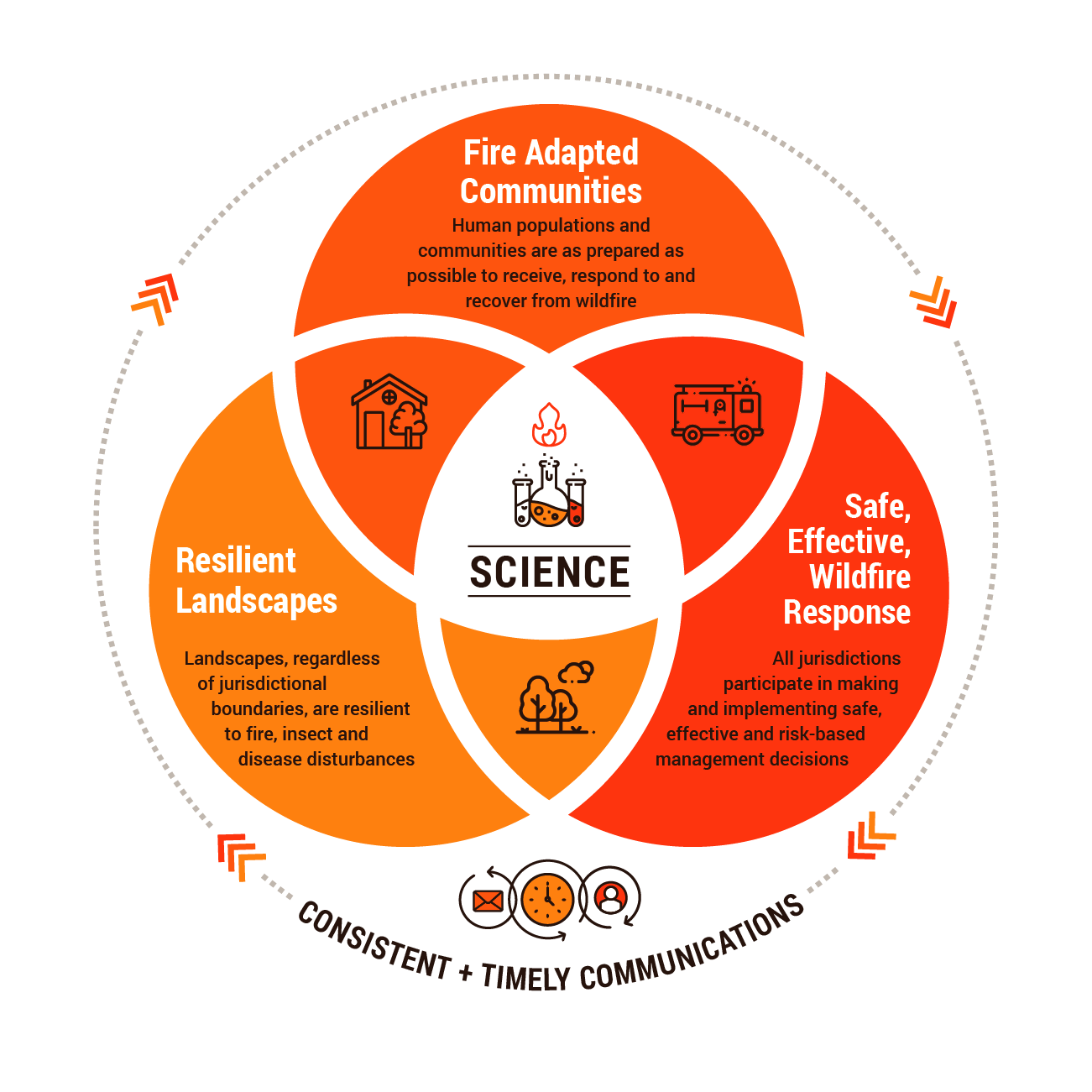

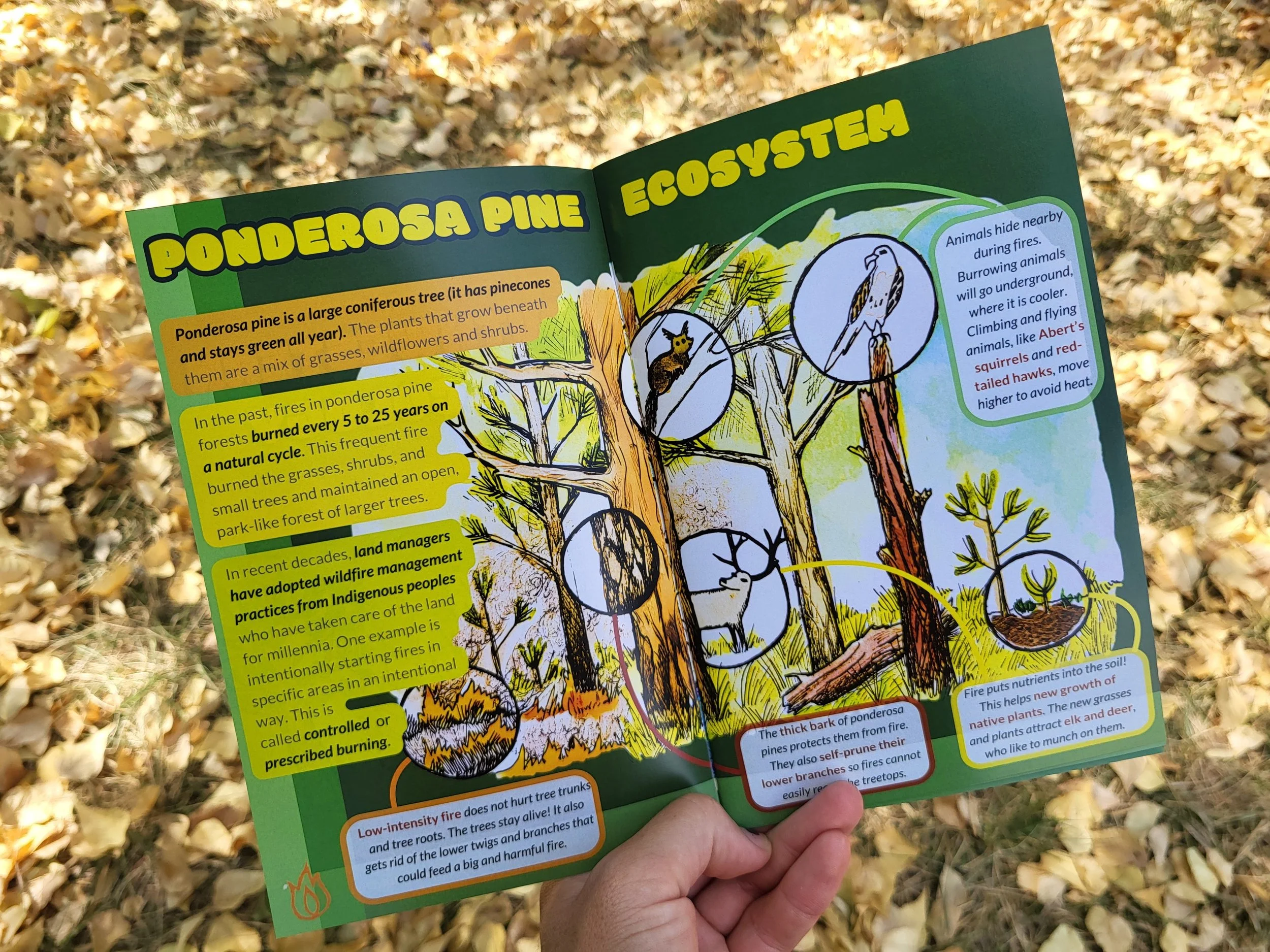

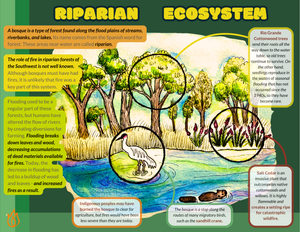

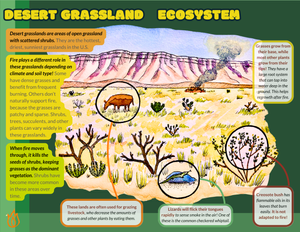

This newsletter often dives into wildfires and fire readiness for communities living in forested areas; however, rangelands (which include grasslands, shrublands, and prairies) cover nearly 60% of all western lands. Fire often plays a critical role in maintaining the health of these grasslands, but also can threaten homes, livestock, and infrastructure. Today’s newsletter touches on how communities can prepare for grassland and prairie fires, especially under windy conditions.

This Wildfire Wednesday features:

Stay safe and be well,

Rachel

Fire in Rangeland WUI

A Growing Risk

“Houses built near wildland vegetation are at greater risk of burning than those farther from the wildland-urban interface, a growing problem as housing developments expand and the climate becomes warmer… The number of homes destroyed by wildfires has doubled over the past 30 years, and most of them were in grasslands and shrublands, not near forests.”

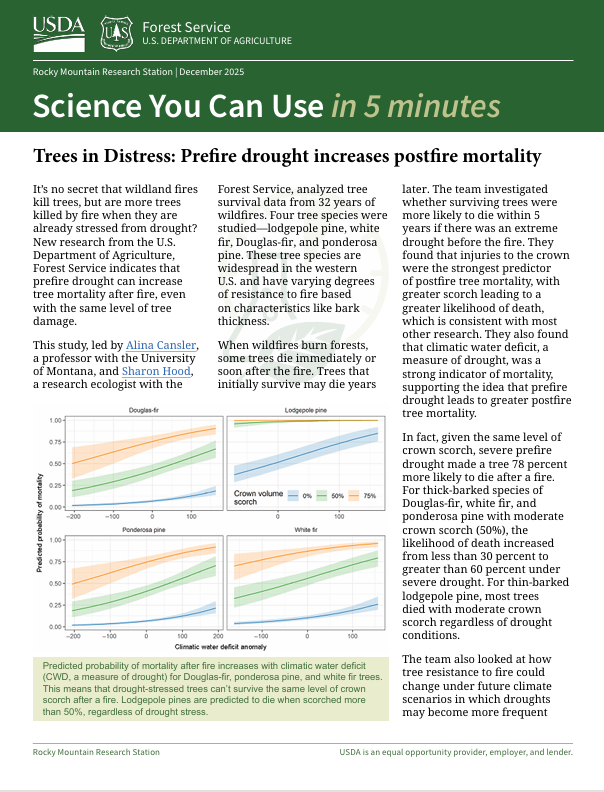

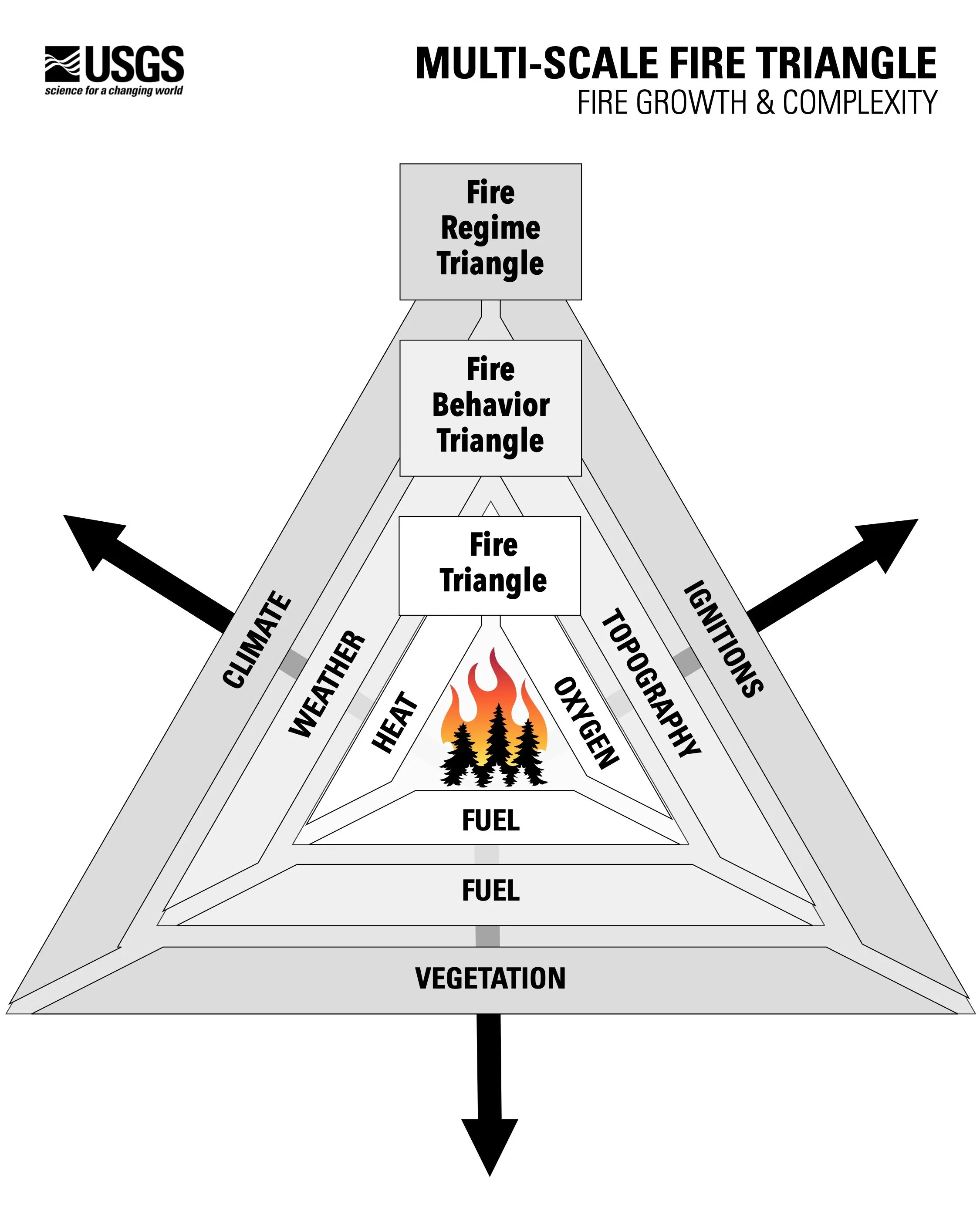

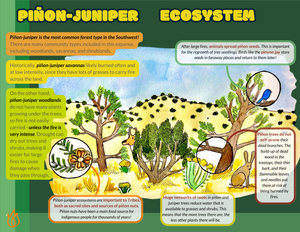

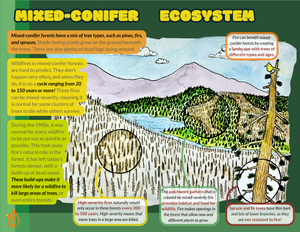

Rapid changes in wildfire patterns have been documented globally. Temperate grassland and savanna biomes have historically been some of the most frequently burned regions on Earth, and we know that fire behaves differently when burning in different vegetation types. “Crown fires in forests have the highest fire intensity and can produce many embers that can ignite houses that are far from a fire front. However, grassland and shrubland fires can spread rapidly when wind is strong, such as in the 2021 Marshall Fire near Boulder, Colorado, which destroyed more than a thousand houses. Furthermore, fuels recover quickly in grasslands and shrublands, such that areas can reburn within a few years, and these areas require different risk management strategies than forests.” (Radeloff et al., 2023). In landscapes where grasses are the predominant vegetative fuel type, these regions are characterized by an abundance of fine fuels and can be particularly vulnerable to wildfire due to their rapid fuel accumulation and high fire frequency.

Fires have historically burned frequently in dry grasslands, returning every 2-10 years. However, increasingly arid conditions, modifications to grass-dominated landscapes, and invasive species have contributed to elevated wildfire behavior and risk. Expanding development and jurisdictional boundaries have fragmented grasslands, increasing the complexity of fire behavior and management and making suppression more challenging. Wildfires occurring in areas predominantly populated by fine rapidly igniting fuels, like those found in grass-dominated landscapes, can quickly impact communities within the Wildland-Urban Interface (WUI) with little forewarning. In such instances, standard predictions of fire spread may not be capable of issuing timely emergency warnings in advance of a fast-moving fire.

“Wet periods (such as monsoonal rains) often lead to heightened production of grass fuels, contributing to an increased risk of extreme fire behavior in subsequent dry years… The accumulation of highly combustible vegetation combined with arid, windy and open landscapes creates favorable conditions for large-scale fires. Although fires can occur at any time of the year the frequency and intensity of these fires depend on factors like precipitation and aboveground productivity (amount of vegetation biomass)… Grass fires can be intense and capable of generating significant heat aboveground. Because grassfires are often rapid spreading surface fires, temperatures peak quickly as fire passes, often killing the tops of living plants including trees leaving belowground vegetation unimpacted” (CSU, Grassland Fuels Management, 2019). Grassland fires are defined as being ‘exceptionally responsive’ to dry, hot, and windy conditions, meaning that grass fires ignited on high fire danger days build heat and speed very quickly.

Watch this video to learn more about how fire behaves in one type of grassland: desert grasslands of the Sonoran and Chihuahuan Deserts.

…………………………….

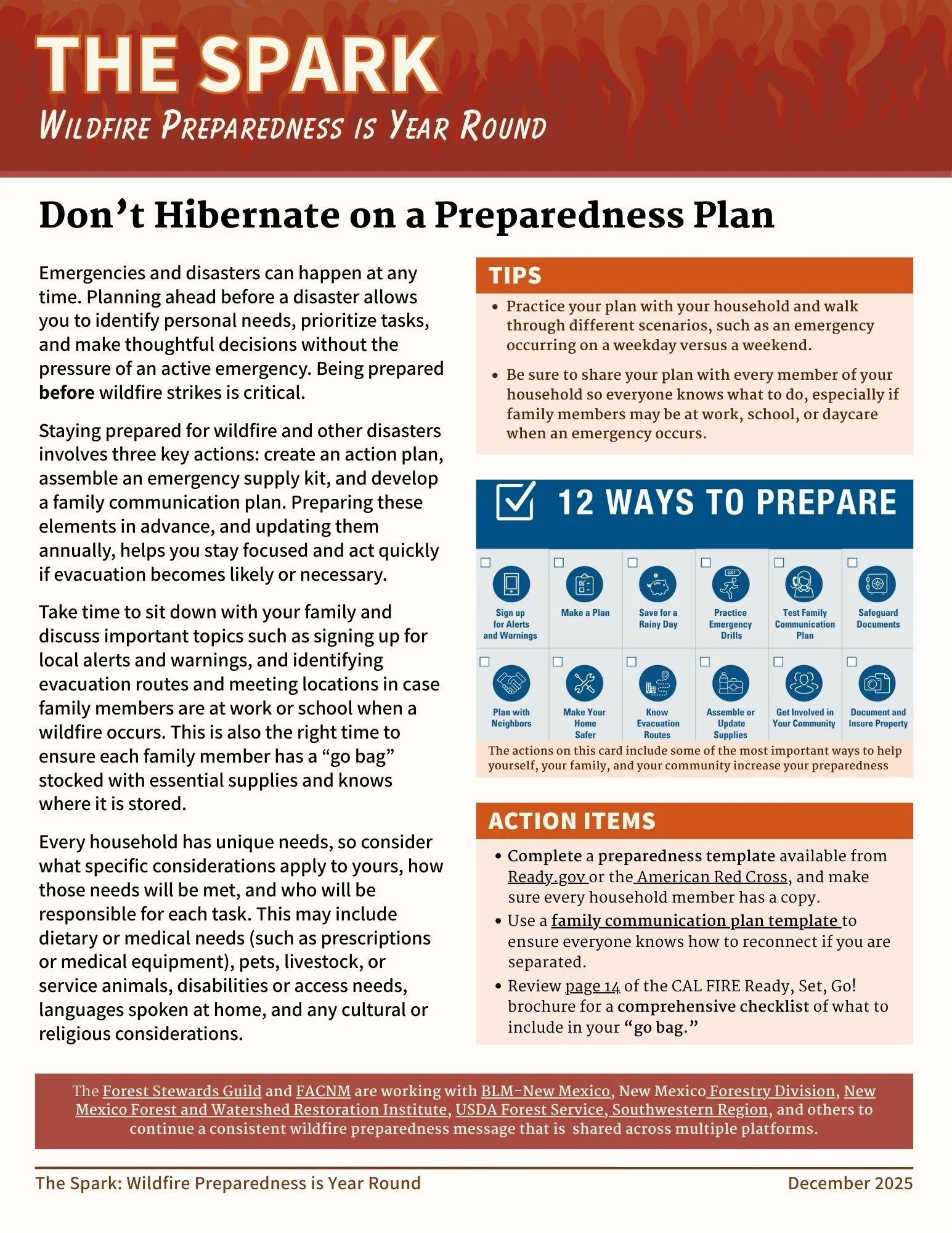

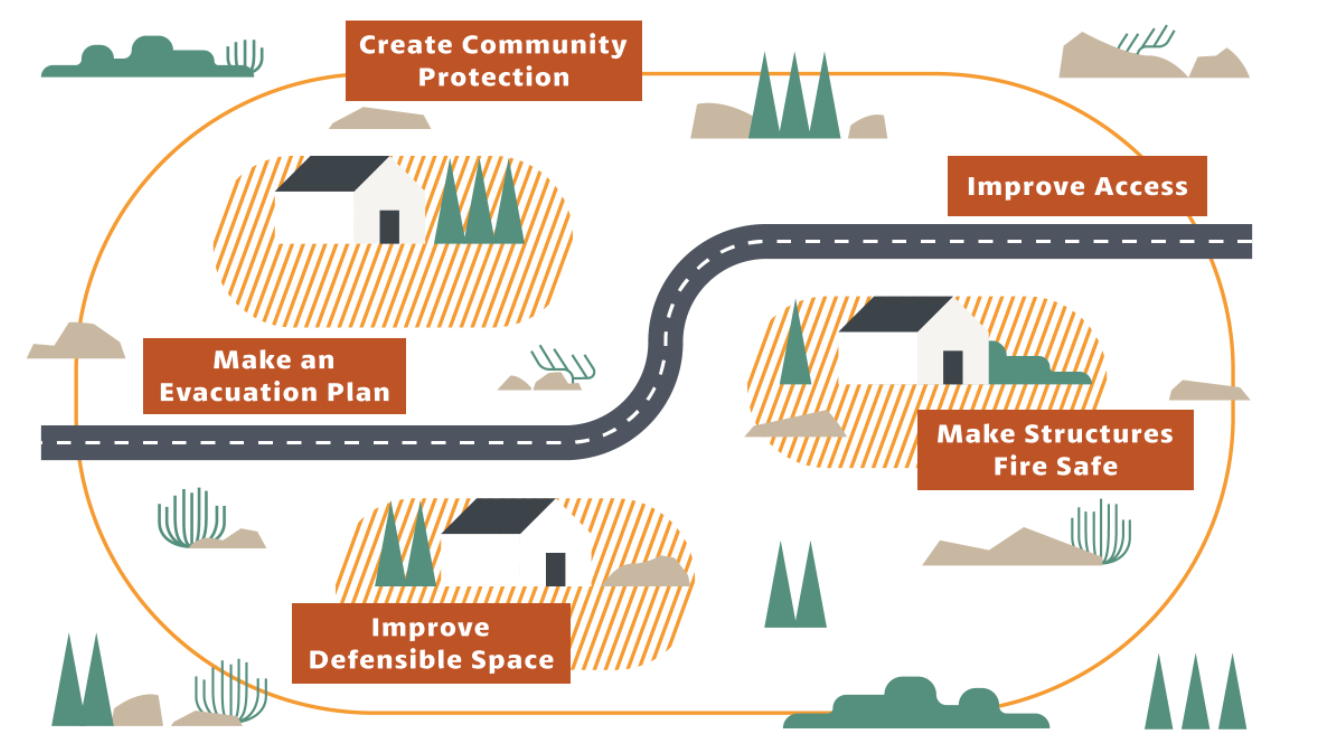

How to Prepare

Some properties have a higher risk for accidental fires, such as those located next to major highways, interstates or railroads. It is unreasonable to think there will be time to prepare property, livestock, equipment and family in the event of wildfire. Landowners should be aware that in the event a wildfire occurs under extreme weather conditions, there may not be enough time or resources available to protect homes and structures. Prepare for grass and rangeland fires by creating defensible space around buildings, knowing how to protect livestock and property, prioritizing your safety, and staying fire aware.

Defensible Space and Property Maintenance

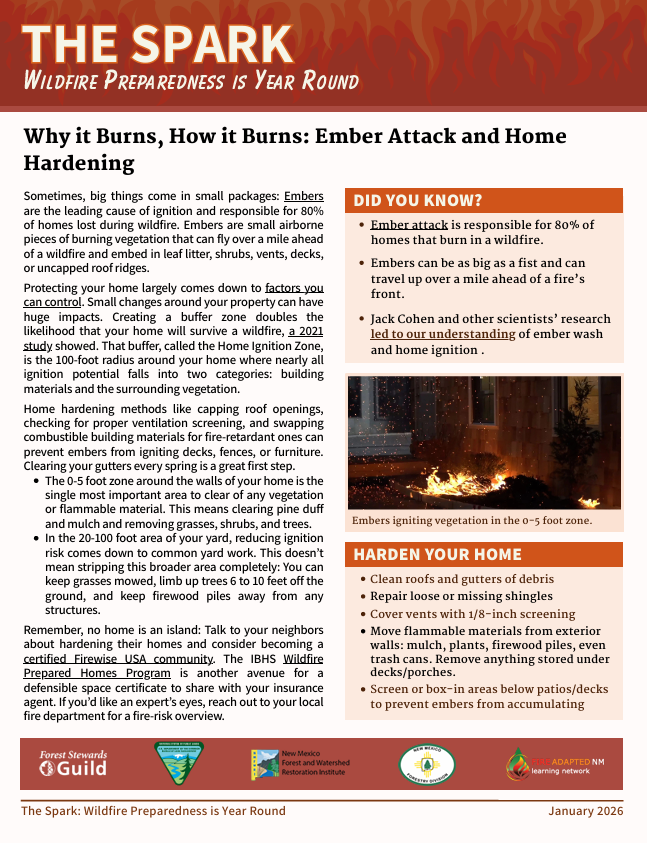

Mow grass: during high fire danger, maintain grass at 4 inches or less, especially within a 30-foot radius of buildings, to minimize fire intensity. Mow grass low around flammable infrastructure, such as wooden fences. Watch this video to see how grass fires behave in mowed vs natural form grass.

Maintain vegetation: prune back trees and shrubs close to buildings ahead of fire season to reduce their flaming potential.

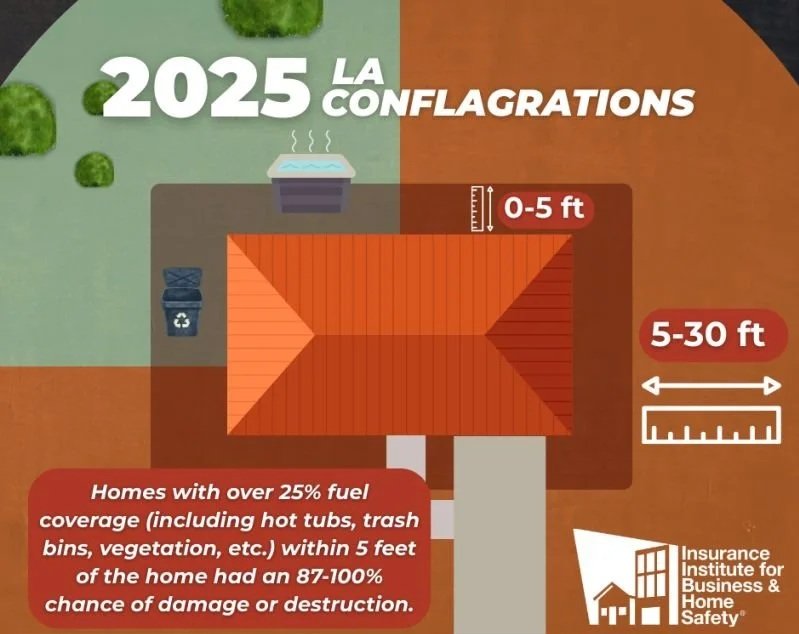

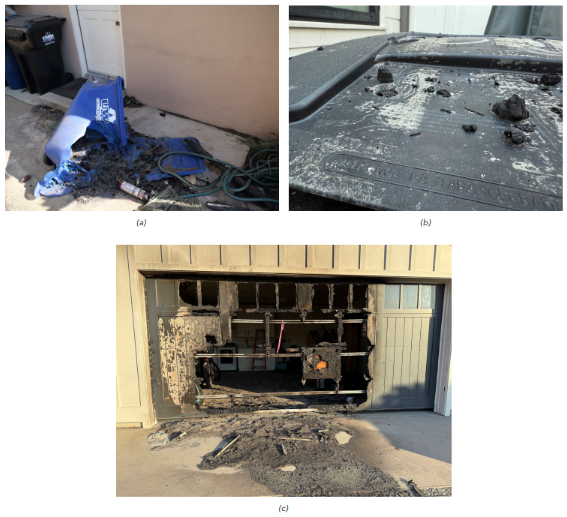

Create a fireproof “zone 0”: protect the area immediately surrounding (0-5 ft away) your home and outbuildings by:

Removing vegetation (grass, trees, shrubs, flowers, etc.) from the area immediately around the house and replacing it with noncombustible (e.g. gravel, crushed stone, or brick) ground cover,

Cleaning roof and gutters by removing leaves and debris and trimming back overhanging tree branches,

Not storing flammable items under deck or patio and moving flammable items (such as cloth cushions or plastic furniture) from porches ahead of a fire,

Moving all flammable materials away from exterior walls, including firewood, mulch, leaves, lumber piles, and other combustible items,

Remove fuel sources: move hay bales, stacked wood, and fuel containers at least 50 feet away from buildings.

Create firebreaks: in strategic areas, firebreaks (a noncombustible protective strip which has been cleared down to bare mineral soil) can be created to impede the path of a fire. However, many wind-driven grassland fires can have horizontal flame lengths exceeding 10 ft and may be able to cross over these barriers.

Preparation for Livestock, Rural Properties, and Insurability

Livestock preparation: **Protecting livestock from wildfire can be dangerous. Entering into an unburned pasture with significant fuel loads and limited escape routes to open gates or cut fences is inherently risky. Be aware of the fire location, direction and rate of spread before making a decision to enter a pasture; if you are unsure, do not enter.**

Maintain gates so they open easily and without tools,

Prepare safe areas for livestock within pastures - maximizing trampling along fence lines and in pasture corners, or creating grazed, paved, or irrigated areas,

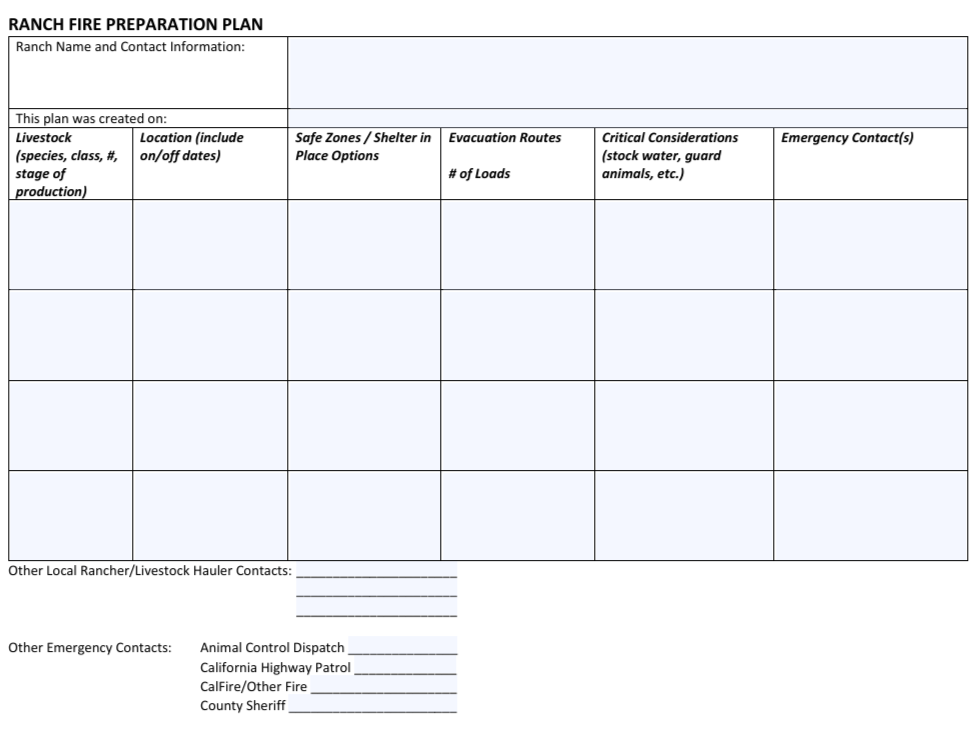

Have a livestock evacuation plan that considers how and where livestock will be taken in the event of a wildfire,

Carry fence pliers to cut a rapid escape route if you find yourself trapped by fire.

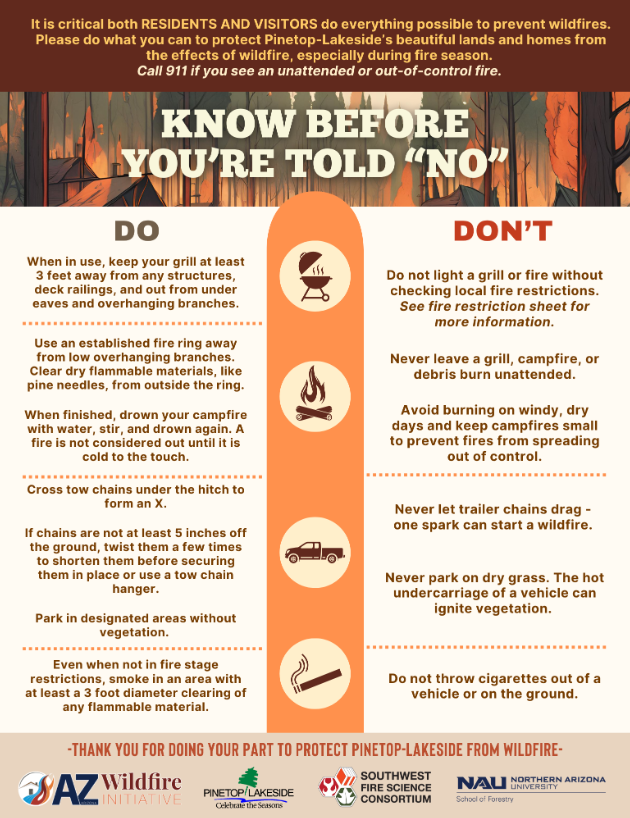

Prevent fire ignitions

Time your mowing: during hot or dry times of the year, mow in the morning when it is cool and moist to avoid sparks from the equipment starting an ignition.

Avoid working on dry days: do not operate equipment which can spark in nearby vegetation during dry, windy, “fire watch,” or "red flag" conditions.

Use proper tools: use weed whackers/string trimmers instead of mowers in rocky areas to avoid sparks. If using this equipment, grass should be mowed to 6 inches or less, rather than 4 inches,

Emergency Planning and Awareness

Stay informed: monitor local weather and sign up for emergency text or email alerts.

Evacuation plan: prepare a "Go Kit" and ensure all family members know the escape routes.

Never approach: if a fire starts, do not try to take photos; leave immediately and call 911.

Beneficial fire

Learn about the role of prescribed or intentional fire in maintaining and protecting grasslands in this publication, this federal guidance, and this webinar recording.

Oklahoma State Extension’s comprehensive fire preparation recommendations and NM Forestry Division provide a lot of additional information on how to prepare for grassland fire; many of these suggestions are applicable to all residents, regardless of where they live, especially recommendations for what to do if a wildfire is approaching and how to prepare to evacuate (see the end of the fact sheet). However, preparation is expensive and demands a lot of time. Start with the simple suggestions (e.g. keeping the grass close to structures mowed during fire season) and build out from there (creating a noncombustible 5’ zone, installing mesh over vents and under porches, etc.).

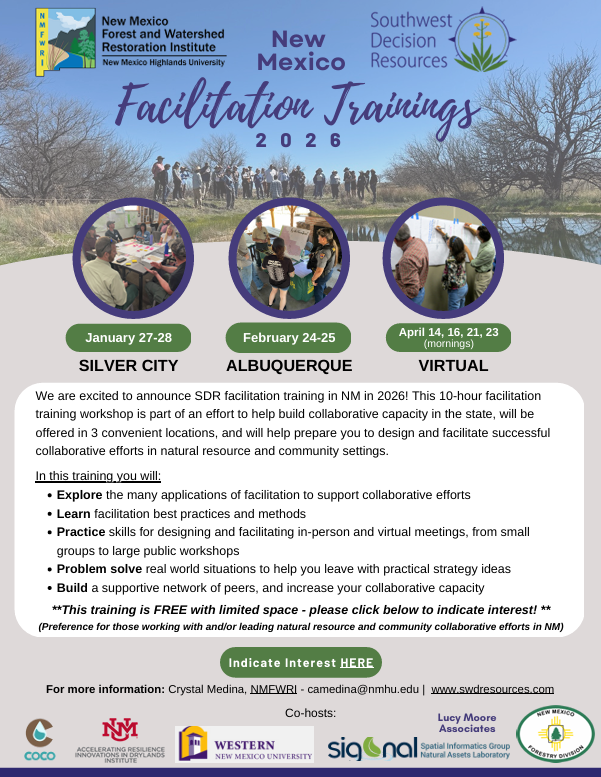

Upcoming Opportunities

FACNM Spring Microgrant

Looking to fund your community fire preparedness event? Apply for a FACNM Microgrant! FACNM Leaders and Members are eligible to apply for grants awards of up to $2,000 to provide financial assistance for:

convening wildfire preparedness events,

enabling on-the-ground community fire risk mitigation work, or

developing grant proposals for the sustainable longevity of their Fire Adapted Community endeavor.

The Spring application period is now open and applications will be accepted through March 20, 2026. Successful applicants will be notified of their award by March 30, 2026.

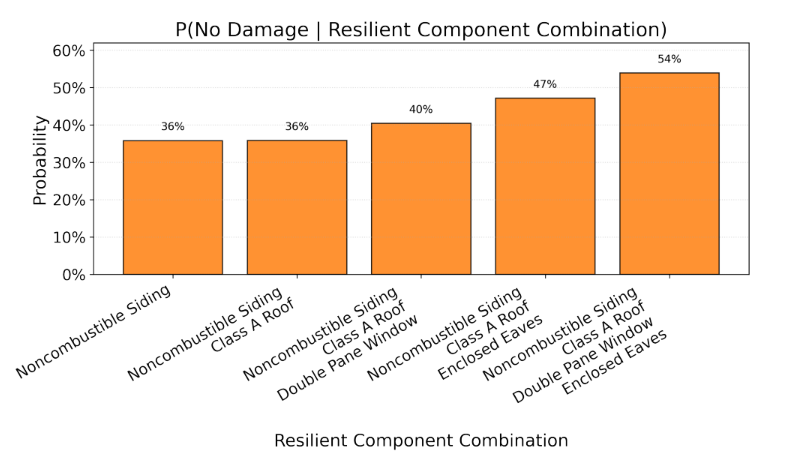

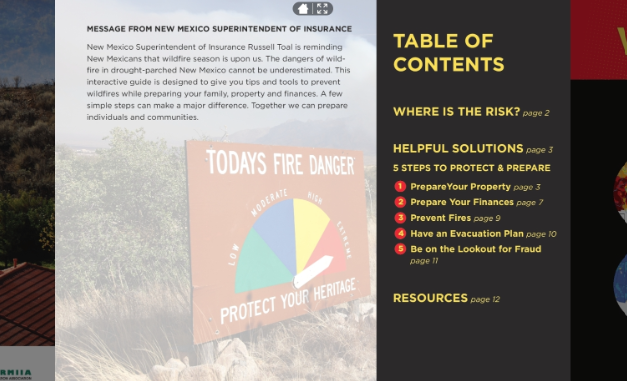

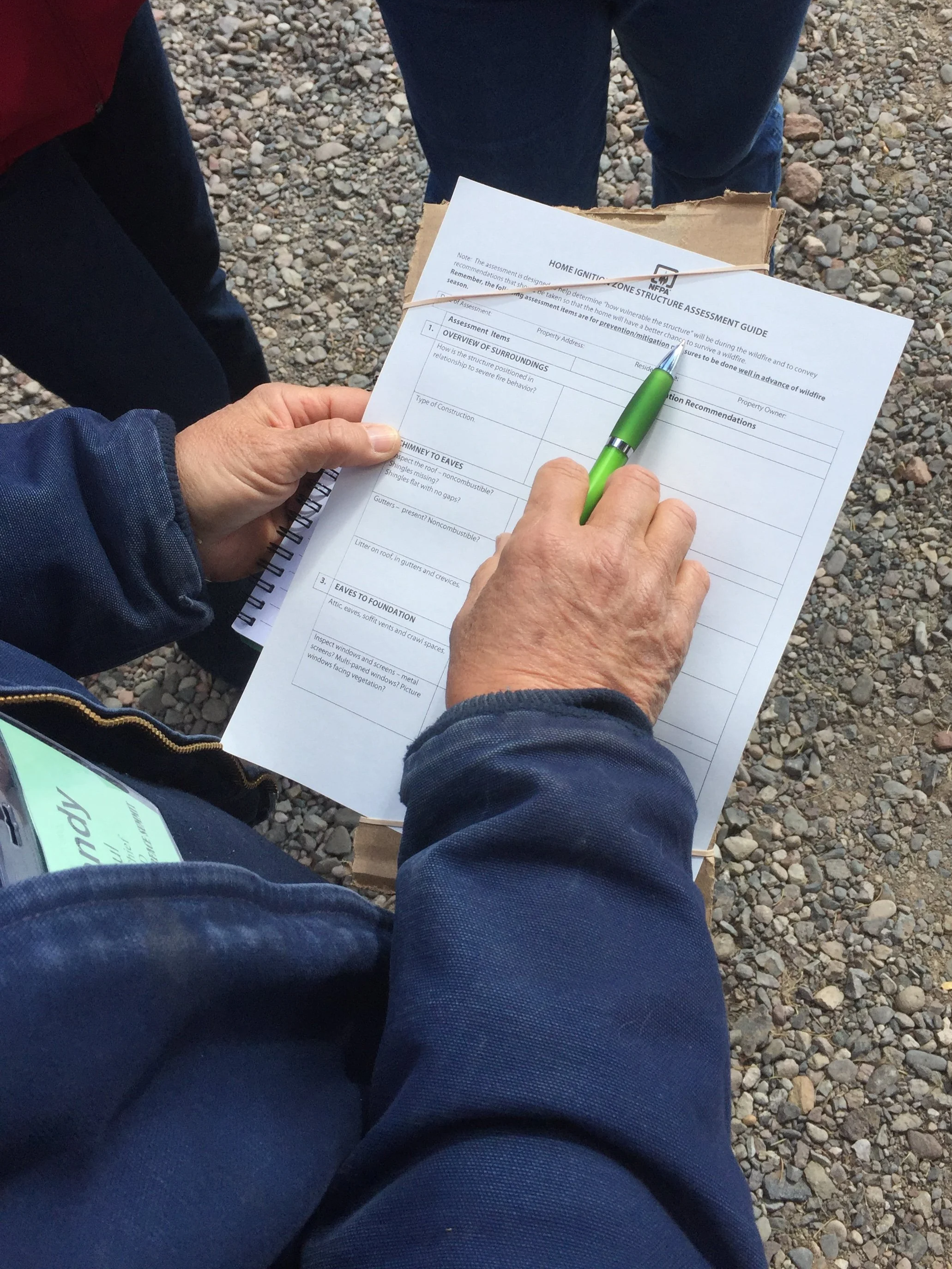

Join FACNM on Tuesday, March 3, 2026 from 12-1 PM for a webinar featuring the New Mexico Office of Superintendent of Insurance (OSI) as they introduce the Wildfire Prepared Home Program. OSI will provide an overview of the program’s key elements and opportunities now available to residents in NM. OSI will share specific actions homeowners can take to harden their homes and improve surrounding property, how these mitigation efforts are evaluated, and how they may contribute to improved insurability in wildfire-prone areas of New Mexico.

The Fire Circle: A Community Fair on Wildfire Mitigation, Response, and Restoration

The New Mexico Forest and Watershed Restoration Institute, Forest Stewards Guild, The Nature Conservancy, New Mexico Forestry Division and Wildfire Resiliency Training Center (WRTC) are hosting a fair-style event, The Fire Circle, at Luna Community College this spring. Attendees will find educational tables and booths, engaging and informational presentations, and family-friendly activities!

This event will provide an approachable space where residents can engage with and access resources related to the full spectrum of wildfire, including mitigation (home hardening, thinning, prescribed fire, etc.), response (suppression, mutual aid, evacuation, etc.), and recovery (forest restoration, community recovery, cascading events, funding, etc.). Please save the date, spread the word, and join us on Saturday, March 21!